Movies and the real-world application of firearms have had a troubled relationship. We go to the movies to escape and to dream, so naturally, some of those flights of fancy wind up being applied to how guns are used in movies, and the hero of the movie winds up shooting 30 or so rounds from a six-shot revolver without reloading.

Nice trick.

For people like me, though, that sort of thing takes me out of the movie. I can only suspend my disbelief so far, so when something happens in the movie like a 30-shot revolver or a hero wasting a platoon of bad guys by hip-firing a machine gun, it takes away from my enjoyment of the movie.

However, the reverse is also true. When a director and stunt coordinator take the time to do things correctly, it adds to my enjoyment of the film. A prime example of this is the iconic bank heist shootout in the 1995 movie “Heat”, where a team of bad guys storm through downtown Los Angeles using real-world fire and movement drills and first-class gun handling.

Heat was directed by Michael Mann, who has a habit of getting the details right about the guns in his movies. The habit began with “Thief”, his directorial debut, where he sent James Caan, the star of the movie, to Gunsite in order to learn the correct way to move and shoot. “Manhunter”, his second movie, featured USPSA Grandmaster Jim Zubiena as an FBI weapons expert. Zubiena went to star in two episodes of “Miami Vice”, performing one of the fastest Failure to Stop drills you’ll ever see on the silver screen.

Hollywood started to realize that on-screen gun battles which had a measure of real-world authenticity to them could also be exciting, and a new emphasis on realistic action was born. The cast of movies like “Saving Private Ryan” and “Black Hawk Down” were shipped to a short “boot camp” of sorts to teach them how to fight as a unit and give them some measure of confidence with the guns they’d be using when the cameras were rolling.

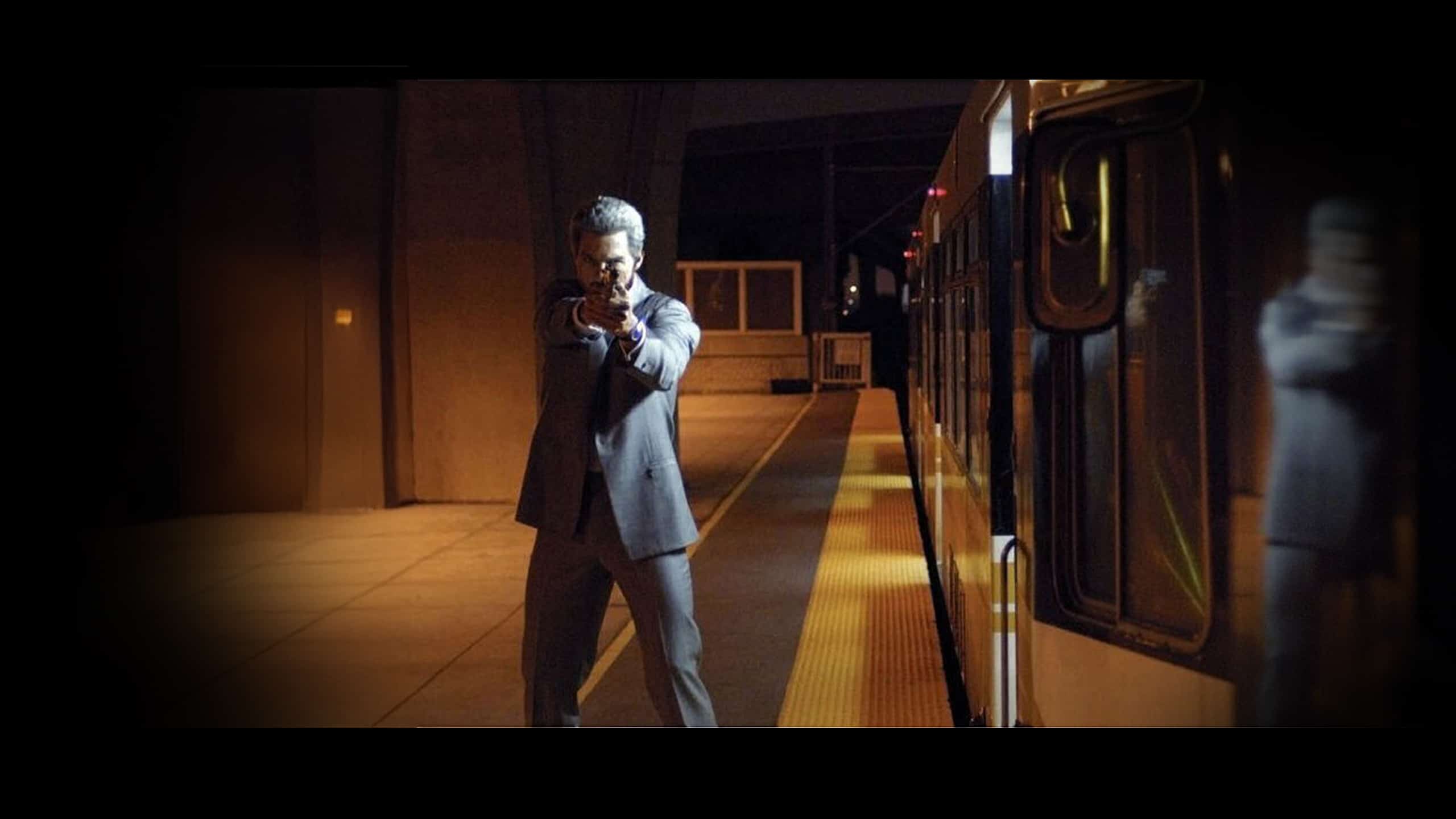

In 2004, Michael Mann returned to the seedier side of life in Los Angeles with “Collateral”, which starred Tom Cruise as Vincent, a hitman on a mission. In the course of doing this, he winds up losing his briefcase to a pair of thugs in an alley, leading to a memorable shootout with a lot of real-world implications.

Let’s break down this gunfight into its distinct parts and see just how it applies to the real-world.

The Setup

Vincent’s case is removed from the back of a cab during a robbery. He challenges the robbers with “Yo, homey, is that my briefcase?” and those thugs then turn around and walk towards Vincent, producing a gun as they do so.

The Challenge

The thugs stop about three feet away from Vincent and demand that he hand over his wallet and watch. One pistol is in play, but another one shows up in the waistband of the thug to Vincent’s right. The other thug is holding his pistol at a 90-degree angle within arm’s reach of Vincent as he makes his demands.

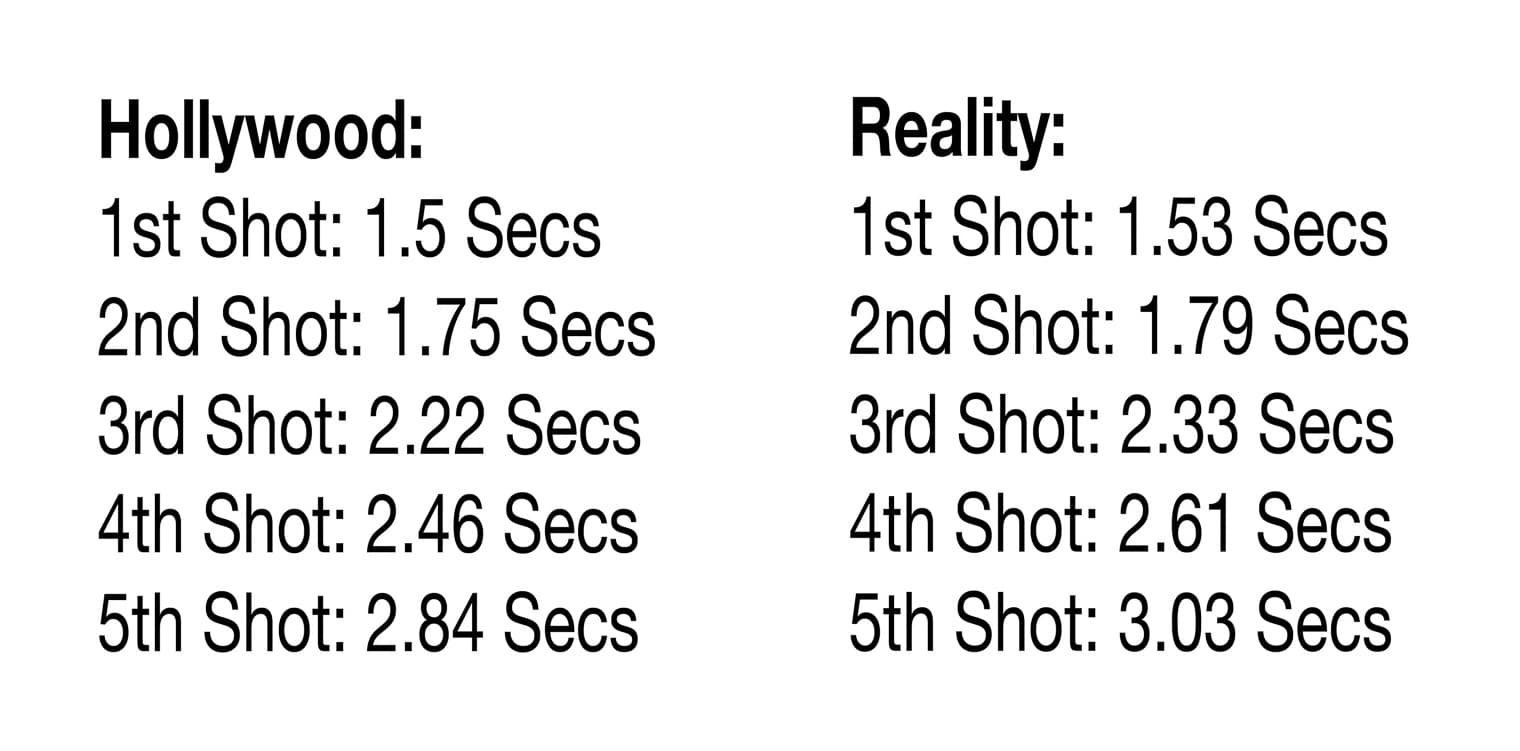

So, how fast does he actually accomplish this drill in “Collateral”? I (legally) downloaded a clip of that scene to my computer and imported it into my video editing suite. By counting the frames between when Vincent first makes a move to his pistol and the final shot on the second badder guy, I’ve come up with the following timeline:

Draw to First Shot: 1.5 Seconds

Vincent bats the badder guy’s pistol out of the way with his support hand and clears his cover garment with a strong side-only one-handed draw. Rather than extend his gun out towards the badder guy and setting up a scenario where the target has a chance to foul the draw, he shoots from Position Two, rotating the muzzle up towards the target immediately after he clears the holster. Besides being faster than pushing the gun out towards the target, it’s also easier to hang onto as it is closer to your body.

Shot Number Two: 1.75 Seconds

Vincent gets off his second shot in just a quarter of a second. Not bad.

Shot Number Three: 2.21 Seconds

Vincent takes some time to move the gun up into his peripheral vision and get a general index of where it’s pointed. He also swings the gun right to line it up with the second target.

Shot Number Four: 2.46 Seconds

Once again, a quarter-second split in between shots. This is possible because Vincent does not have to verify his sights are on target when he pulls the trigger. He’s so close, he literally cannot miss.

Shot Number Five: 2.84 Seconds

It takes Vincent a few fractions of a second to raise the gun until it’s aligned with the ocular cavity, then press the trigger.

Vincent calmly picks up his briefcase, does a coup de grace shot on the first thug, and then walks back to his waiting vehicle. It’s important here to remember that Vincent is a bad guy, and taking that final shot on a downed, defenseless opponent shows his character.

For those of us who choose to obey the law, however, this is an excellent on-screen portrayal of how a resource predator operates. A resource predator uses violence (or the threat of violence) to get what they want, be it a briefcase, a wallet, or some other item we may have. Vincent did not expect the gun to appear in the thug’s hand, and when it did, he had to come up with a Plan B quickly. In his case, Plan B was to wait for an opening and counter the threat of lethal force with lethal force of his own.

Realistic, or Not?

But how much of this is Hollywood magic, and how much is real life? Can a reasonably well-trained armed citizen duplicate this sort of performance without a stunt coordinator and a special effects house? Let’s find out.

Let’s start with the hardware. Tom Cruise uses a large, duty-sized pistol chambered in .45 ACP. Hiding that big of a gun under a suit jacket is, to say the least, a challenge, and to say the most, it’s Hollywood magic, not real life.

Instead, for my test, I would use a much more suitable concealed-carry option: a Springfield Armory Hellcat Pro. I am a huge fanboy of using leather holsters for outside-the-waistband carry, so I’m carrying that pistol in a DeSantis Mini Scabbard holster. Ammunition will be Blazer Brass 124-gr. FMJs, and my cover garment is a Perry Ellis suit jacket, because I’m certain you were wondering about that particular detail.

Let’s pause for a moment and return to the question of a Mozambique Drill versus a Failure to Stop Drill. The classic Mozambique Drill is two shots to the center mass, a measurable pause to evaluate the effect of those shots on your target, then a shot to the upper ocular cavity to stop the threat.

This is different from the Failure to Stop Drill as created by the LAPD SWAT team. A Failure to Stop Drill does not include the pause between the first two shots, and this is the version our (anti-)hero demonstrates in the movie.

How Did I Do?

Not bad at all considering that a.) I shot it cold, with no warm-up, and b.) I backed up from the “bad guys” as I shot, while in the Hollywood version, Vincent/Tom Cruise stayed in one place.

I shot this drill cold because that’s the way an armed citizen would do it. We don’t have the luxury of calling out “CUT!” and re-doing the shot if something isn’t right. On a related note, I backed up away from the bad guys because distance works in my favor, not theirs. If the area had been more crowded, I would have stayed in one place rather than risk backing into something and falling down.

Did Hollywood get it right? In my opinion, yes, it looks like they did, at least this time. I’m certainly impressed!

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply