In 2017, the Chilean government approved a $2.5 billion expansion of BHP’s Spence copper mine — the diversified miner’s second largest copper mine behind Escondida. In 2020, BHP became the top shareholder in SolGold (TSX:SOLG), an Australian miner developing the Cascabel copper-gold project in Ecuador. In 2021, chief executive Mike Henry said the company needs more “future-facing metals” such as copper.

Two years later, BHP Group (NYSE:BHP), the biggest mining company in the world by market capitalization ($142 billion as of the latest close) was bidding on Anglo American (LSE:AAL), eager to snatch the UK-based miner’s copper assets in Chile and Peru, namely Los Bronces, Collauhuasi, El Soldado and Quellaveco.

While the deal ultimately failed, the fact that BHP was willing to pay $39 billion for Anglo’s copper mines says a lot about the importance of copper to the electrified economy, and the companies that mine it.

As this article will prove, it isn’t only BHP that is hunting for copper, which is now the most critical mineral on Earth due to it being a required raw material in electric vehicles and renewable energy, yet in increasingly short supply.

Indeed the entire supply chain — from upstream miners to downstream users, and everything in between, including majors, mid-tiers, juniors and copper smelters — is screaming for copper, trying desperately to lock up supply before the world runs out, as demand overtakes available quantities as early as next year.

Copper

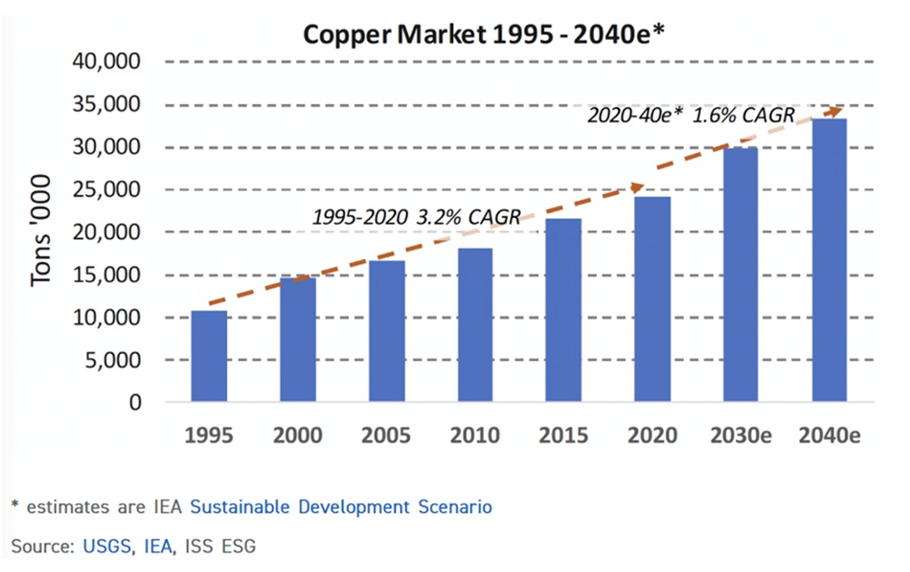

Copper is one of the most important metals with more than 20 million tonnes consumed each year across a variety of industries.

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for the base metal even further.

Simply put, electrification doesn’t happen without copper, the heartbeat of the global energy economy.

Along with the usual applications in construction wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, there is now added demand for copper in electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

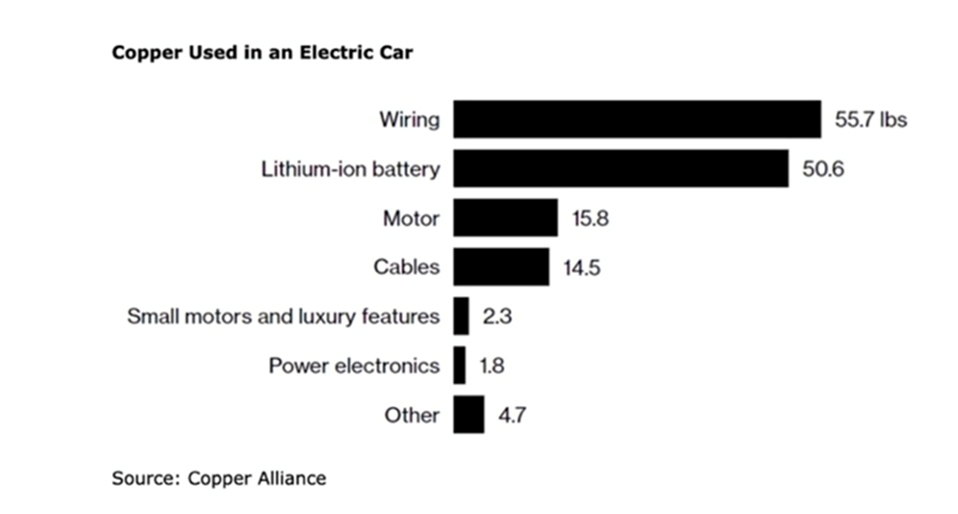

Millions of feet of copper wiring will be required for strengthening the world’s power grids, and hundreds of thousands of tonnes more are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use triple the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars. There is more than 180 kg of copper in the average home.

Additional copper is being demanded by the electrification of public transportation systems, 5G and AI.

Depletion & production problems

Production concerns spread to MSM late last year, when the government of Panama ordered First Quantum Minerals (TSX:FM) to shut down its Cobre Panama operation, removing nearly 350,000 tonnes from global supply.

A strike at another large copper mine, Las Bambas in Peru, temporarily halted shipments.

Copper specialist Anglo American now says it is scaling back output by about 200,000 tons, owing to head grade declines and logistical issues at its Los Bronces mine. Los Bronces production is expected to fall by nearly a third from average historical levels next year as the miner pauses a processing plant for maintenance, Reuters said Tuesday.

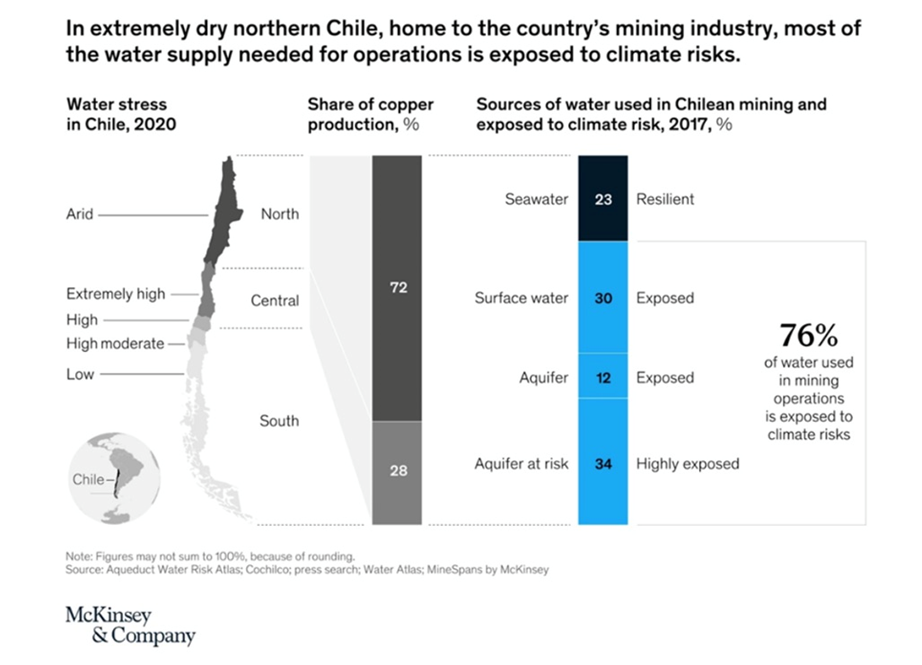

Chile’s copper output has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north. State miner Codelco’s 2023 production was the lowest in 25 years.

All four of Codelco’s megaprojects have been delayed by years, faced cost overruns totaling billions, and suffered accidents and operational problems while failing to deliver the promised boost in production, according to the company’s own projections.

There are also concerns about Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, where drought conditions have lowered dam levels, creating a power crisis that threatens the country’s planned copper expansion.

Ivanhoe Mines (TSX:IVN) reported a 6.5% quarterly drop in production at the world’s newest major copper mine, Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC.

The tightness of the copper concentrate market has been reflected in treatment and refining charges plummeting from over $90 per tonne to below $10/t. This drastic reduction compelled Chinese smelters, responsible for around half of global refined copper production, to consider a 10% production cut.

In a previous article, we dug deep into the supply cuts to get an idea of how much copper is actually being produced. Our analysis confirmed suspicions that it is considerably less than a few years ago.

Biggest copper mines produced 20% less copper in 2023

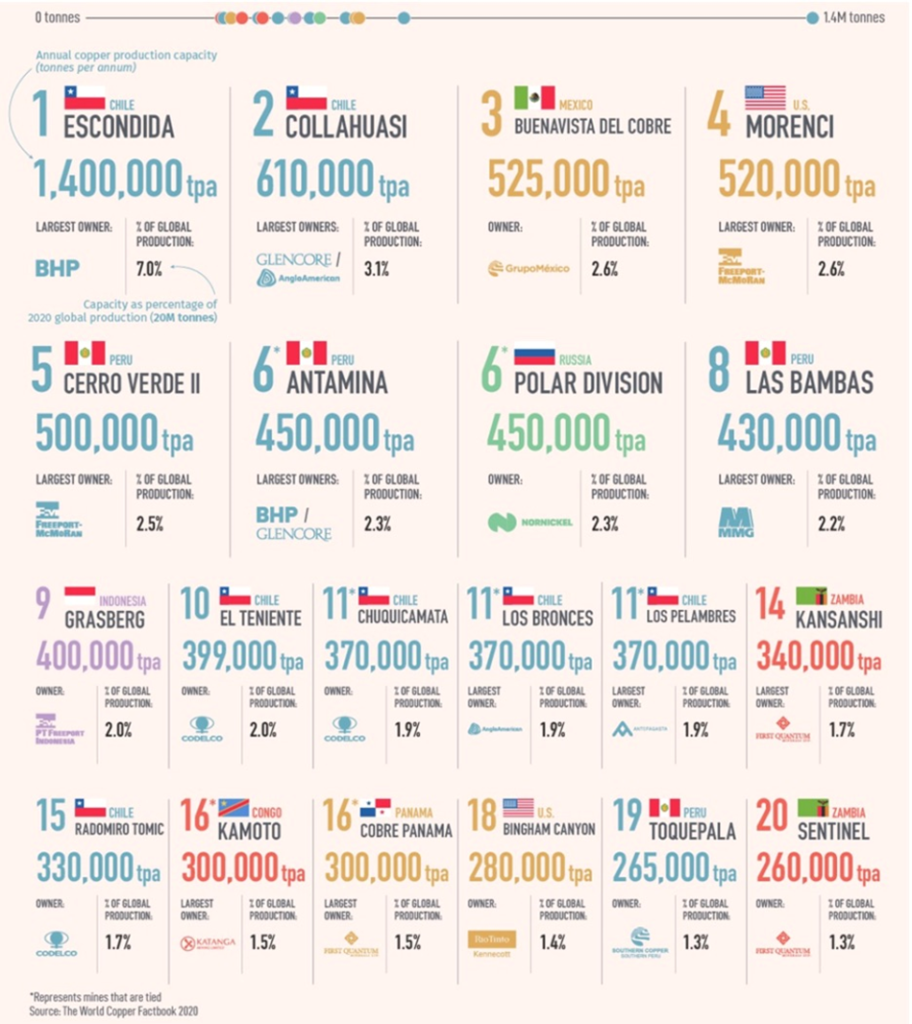

Our first step was consulting Visual Capitalist’s 2021 graphic of the world’s 20 largest copper mines by production capacity.

The figure below shows Escondida in Chile leading the pack, at 1.4 million metric tons capacity per annum, through to number 20 First Quantum’s Sentinel mine in Zambia with its 260,000 tpa capacity. Five of the 20 mines “tied” for having the same amount of capacity.

Source: Visual Capitalist

Source: Visual Capitalist

These 20 mines have the capacity to produce nearly 9 million tonnes of copper annually, representing 44% of global production in 2020.

But how much did they actually produce in 2023?

AOTH combed through quarterly and annual reports, press releases and news articles to find out.

Of the mines we could find 2023 production figures for, the total came to 5,818,792 tonnes. Only two — now-shuttered Cobre Panama and Grasberg (Freeport McMoRan’s 231,836t +204,960t estimated production from PT Inalum and PT Indonesia based on 51.24% ownership) — produced more than their 2020 production capacities. The rest produced less.

We had to find a way to compensate for the missing data for six mines. We decided to use each individual mine’s 2020 production capacity as the (missing) 2023 production figure. For example, no figures were found for Southern Copper’s Buenavista mine in Mexico, so for 2023 we used its 2020 production capacity of 520,000 tonnes. This generously estimates the amount of copper that was actually produced last year, since most, if not all of these mines with missing data likely produced less than their production capacity.

Adding 1,592,960 tonnes of estimated 2023 production (for six mines) to the 5,818,792 tonnes of actual 2023 production for the remaining 14 mines gives a total of 7,411,752 tonnes — 19.6% less than 2020’s total capacity for the world’s top 20 mines of 8,869,000 tonnes.

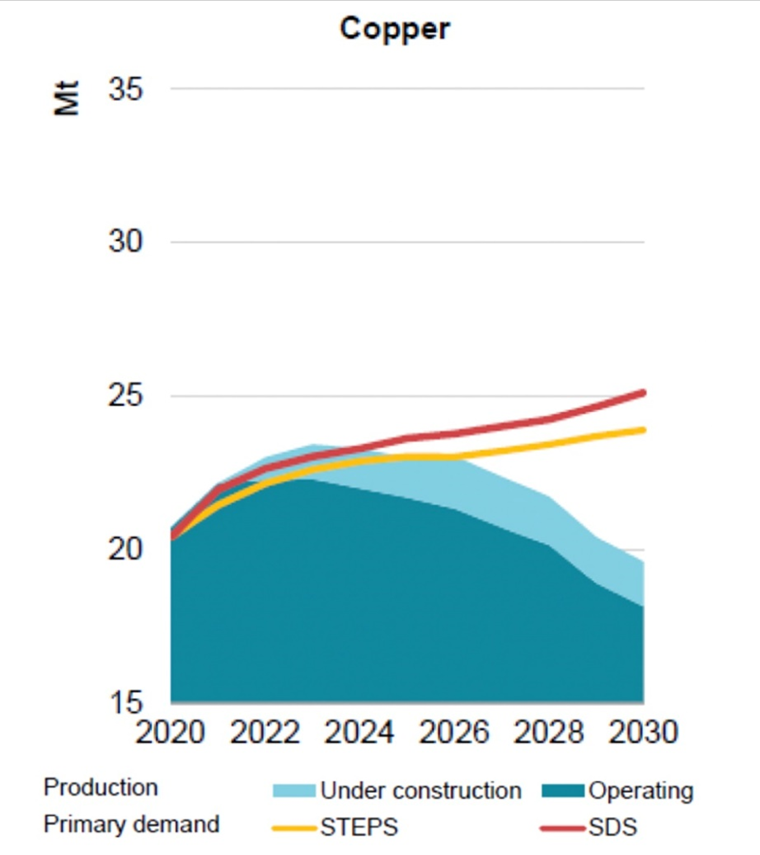

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI) forecasts global copper consumption to grow 3.5% to 28 million tonnes in 2024, and for demand to increase from 27 million tonnes in 2023 to 38 million tonnes in 2032, averaging 3.9% yearly growth.

Yet the US Geological Survey reports supply from copper mines in 2023 amounted to only 22 million tonnes. If the copper supply doesn’t grow this year, we are looking at a 6Mt deficit.

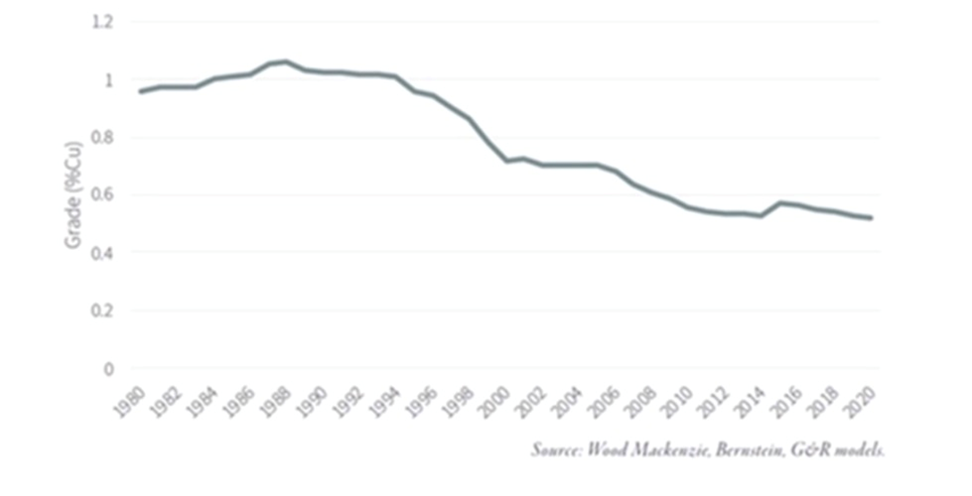

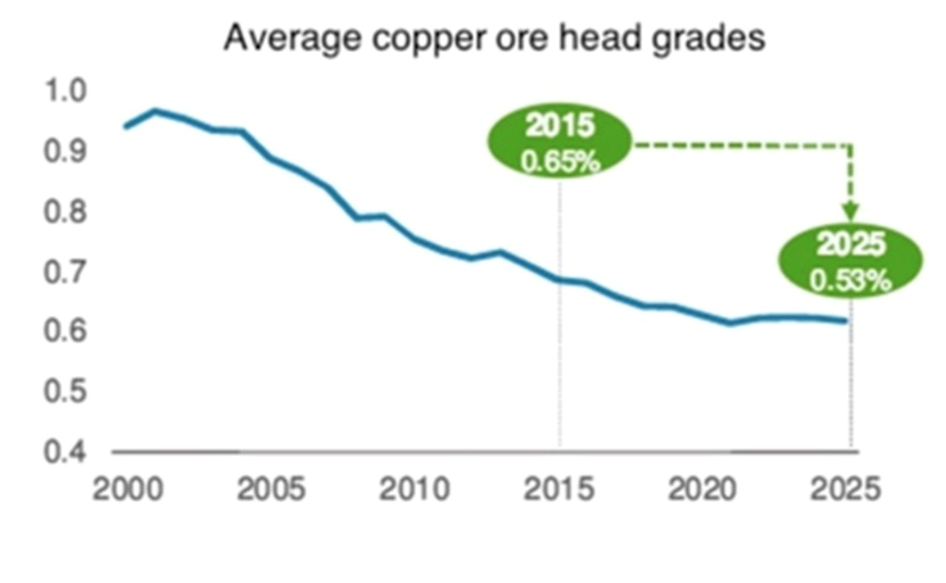

As our calculations show, that 22 million tonnes of production reflects roughly a 20% reduction in output from the top 20 copper mines. If supply interruptions continue in some of the top producers, like Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, the deficit could grow even bigger, and likely will. More labor unrest at Las Bambas in Peru is looming. Chile continues to have water problems and according to the International Energy Agency, average copper grades there have declined by 30%.

Wall Street commodities investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg says the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution. If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all.”

The importance of making new discoveries in establishing a sustainable copper supply chain is obvious.

Exposing the copper surplus myth — Richard Mills

Greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

Average grade of remaining copper reserves

Average grade of remaining copper reserves

Copper discovery cupboard bare

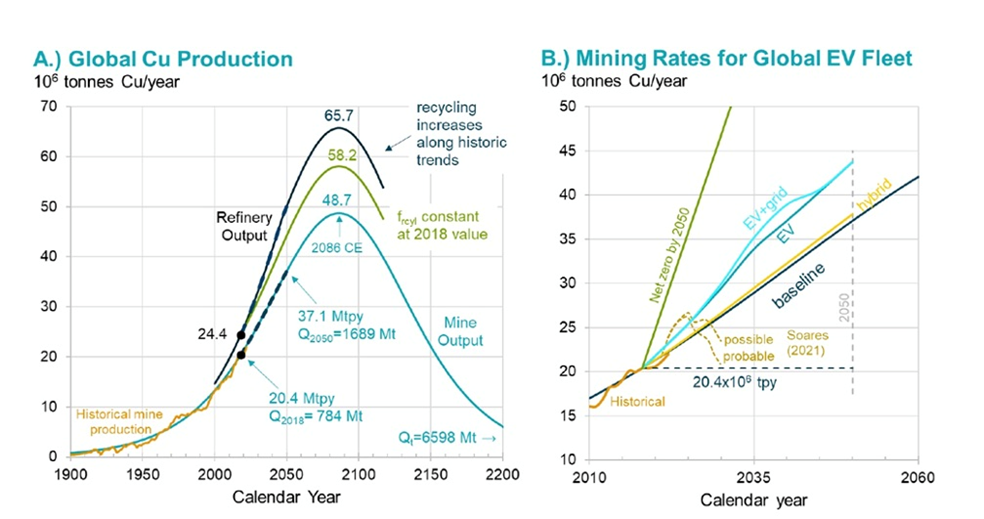

Bloomberg New Energy Finance says copper miners need to double the amount of global copper production, just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles — from the current 22Mt a year to 40Mt.

Copper consumption by green energy sectors globally is expected to jump five-fold from 2020 to 2030, data from consultancy CRU Group shows.

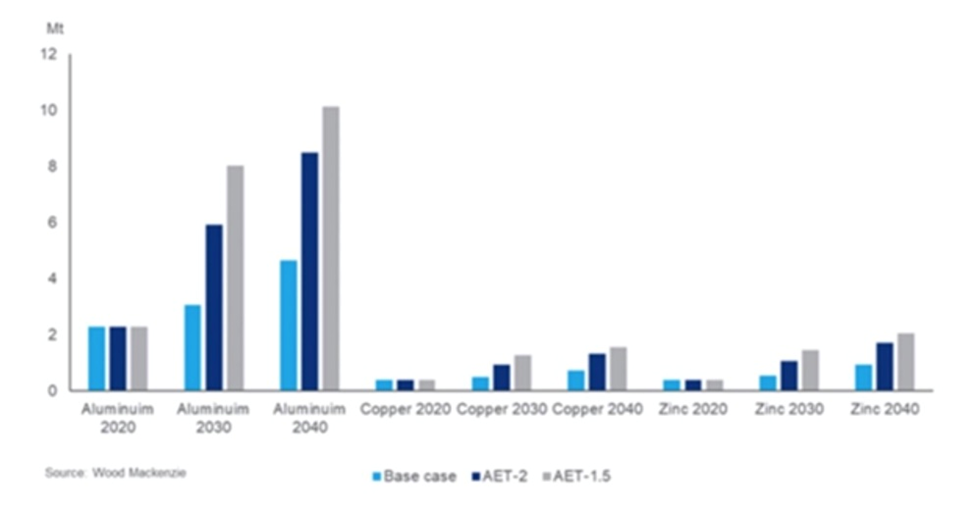

Future copper usage is closely tied to meeting carbon emissions targets.

To transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to one run on clean power including the electrification of the global transportation system, will require a colossal boost in the production of mined materials, including copper.

Higher penetration of solar, wind and energy storage all will require copious metals.

Wood Mackenzie, a commodities consultancy, predicts that usage of aluminum, copper and zinc in photovoltaics will double by 2040.

“Copper is used in high and low voltage transmission cables and thermal solar collectors,” Kamil Wlazly, Wood Mackenzie’s senior research analyst, wrote in the report.

Under a base case scenario, consistent with a 2.8 to 3˚C global warming view, the report expects aluminum demand from solar to rise from 2.4 million tonnes in 2020 to 4.6Mt in 2040; base case copper demand would go from 0.4Mt in 2020 to almost 0.7Mt; and global zinc consumption would double from 0.4Mt 0.8Mt in the base case.

There are two ways for the mining industry to increase copper reserves: it can either find large new deposits to develop into mines; or copper companies can lower their cut-off grades and add new reserves that way.

Some of the world’s largest copper companies are doing everything they can to expand existing mines and acquire prospective new deposits, as they seek to replace their rapidly depleting copper reserves and resources.

We’ve already mentioned BHP’s interest in copper, evidenced by its $39B bid for Anglo American last year.

Anglo has indicated that South Africa would be a good jurisdiction to explore. Copper, nickel, lead, and zinc are among the base metals the company is focusing its global discovery strategy in greenfield and brownfield projects.

Barrick Gold (TSX:ABX) wants to diversify into the red metal from the yellow. The company already owns the Porgera mine in Papua New Guinea, which borders Indonesia to the east, with China’s Zijin Mining.

Another big gold miner, Newmont Corp (TSX:NGT), in 2021 struck a deal with GT Gold, to take over the junior and its Tatogga gold-copper discovery in the Golden Triangle of northwestern British Columbia.

Why are major mining companies so intent on securing new supplies of copper? Quite simply, they are running out of ore.

Without new capital investments, Commodities Research Unit (CRU) predicts global copper mine production will drop from the current 22 million tonnes to below 12Mt by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15Mt. Over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle; they are having to dramatically slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground. Examples include the world’s two largest copper mines, Escondida in Chile and Grasberg in Indonesia, along with Chuquicamata, the biggest open-pit mine on Earth.

These cuts are significant to the global copper market because Chile is the world’s biggest copper-producing nation — supplying 30% of the world’s red metal. Adding insult to injury, copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade, bringing less ore to market.

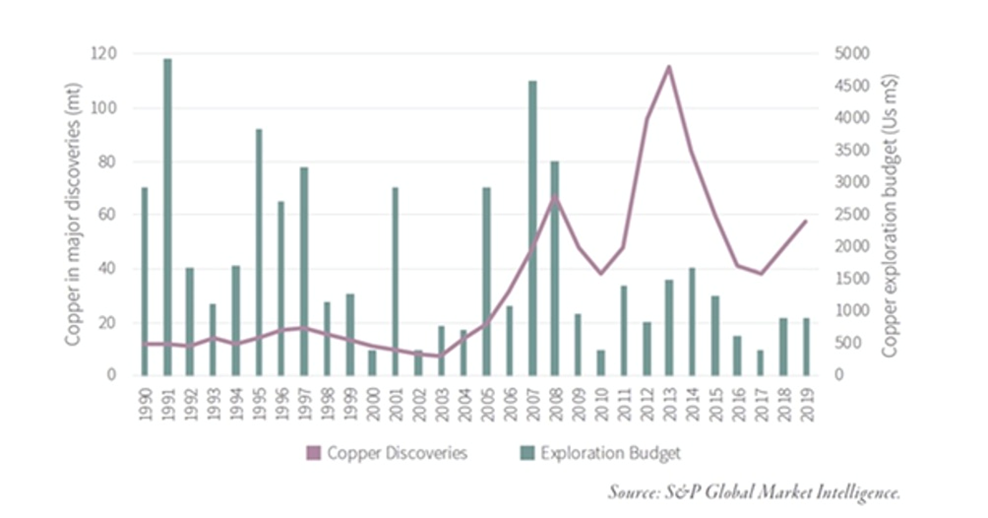

Greenfield and brownfield reserve additions are expected to disappoint through the decade, according to Goehring & Rozencwajg. S&P Global Market Intelligence estimates that new discoveries averaged nearly 50Mt annually between 1990 and 2010. Since then, new discoveries have fallen by 80% to only 8Mt per year. (I would actually be surprised if 8Mt of copper is being found annually. It is likely considerably less — Rick)

Copper discoveries and capital expenditures

Copper discoveries and capital expenditures

The degree to which the industry has failed to bring on new mines is evident in a new study by the University of Michigan and Cornell University. The researchers found that copper can’t be mined fast enough to keep up with current US policy guidelines to make the transition from fossil-fueled power and transportation to electric vehicles and renewable energies.

How impossible? The researchers found between 2018 and 2050, the world will need to mine 115% more copper than has been mined in all human history to 2018. This would meet our current copper needs and support the developing world without considering the green energy transition.

To electrify the global vehicle fleet requires bringing into production 55% more new mines. Between 35 and 195 large new copper mines would have to be built over the next 32 years, at a rate of up to six mines per year. Spoiler alert – ain’t gonna happen, in other words an impossible task. In heavily regulated environments like the United States and Canada, it can take up to 20 years to build one mine from scratch.

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

China

Their reserves dwindling, head grades lower, a lack of new discoveries, and production snafus due to a litany of problems including indigenous relations, NGO’s, resource nationalism, global warming/ power cuts and shortages of water is it any wonder that countries (and companies) needing copper are looking elsewhere for it?

The posterchild for this trend is China, which in the 1990s and early aughts, went shopping for the minerals it needed to feed its economy that, until 2015, was growing at double digits. Beijing invested billions either through the purchase of mining and energy company stakes, or outright mine acquisitions. At first, the buys were concentrated in Africa, with iron ore and copper the predominant commodities.

The idea was that deep-pocketed, state-funded miners would buy projects for China’s domestic use.

The purchase in 1998 of an 85% stake in Zambia’s Chambishi copper mine for about $20 million was one of China’s earliest overseas mining investments.

China announced a $5 billion loan to the DRC for infrastructure development in 2007, following up another $3.8 billion for mining investments in 2008. The Export-Import Bank of China pledged a nearly $9 billion loan to build and upgrade the DRC’s road (4,000 km) and rail system (3,200 km) for transportation routes that connect its extractive industries, and to develop and rehabilitate the country’s mining sector, in return for copper and cobalt concessions. China would gain rights to extract up to 10 million tons of copper and 420,000 tons of cobalt (proven deposits) over a 15-year period.

The China Non-Ferrous Metals and Construction (CNMC) and Yunnan Copper Industry in 2013 commissioned a $300 million copper smelter in Zambia’s Chambishi. (Institute of Developing Economies Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO))

More recently the desired metals are those that feed into the global shift from fossil fuel-powered transportation and energy generation to electric cars and renewables. This has meant a search for lithium, cobalt, graphite, copper and rare earths.

How China is locking up critical resources in the US’s own backyard

As part of a plan to reduce debt, Rio Tinto (LSE:RIO) put its Northparks copper-gold mine in Australia on the block. China Molybdeum Co answered the call, in 2013 paying $820 million for 80% of the asset.

In the early 2010s, China began moving into South America. State aluminum company Chinalco bought the Toromocho copper mine in Peru from a junior, Peru Copper, and began commercial production in 2010. Chinalco still owns the mine and in 2018 started an expansion.

In 2014 a consortium of three Chinese companies — CITIC Metal Co., MMG and Guoxin — acquired the Las Bambas copper mine in Peru from Glencore Xstrata in an all-cash deal worth $5.85 billion.

Japanese companies got in on the action too. A news report from 2013 said JX Nippon Mining & Metals was on track to more than double copper production from its mines, the majority coming from JX’s 75%-owned Caserones copper mine in Chile. (the mine is now 51% owned by Lundin Mining – see below)

In 2020, Mitsubishi Materials was also active in Chile, agreeing to acquire a 30% interest in the Montoverde copper mine and associated projects from Mantos Copper for $263 million. The other 70% is held by Capstone Copper (TSX:CS).

A third Japanese company, Marubeni, holds a 30% stake in the Centinela and Antucoya copper mines and a 12.48% stake in Los Pelambres copper mine, all of which are in Chile. Marubeni operates the mines with Antofagasta plc (LSE:ANTO).

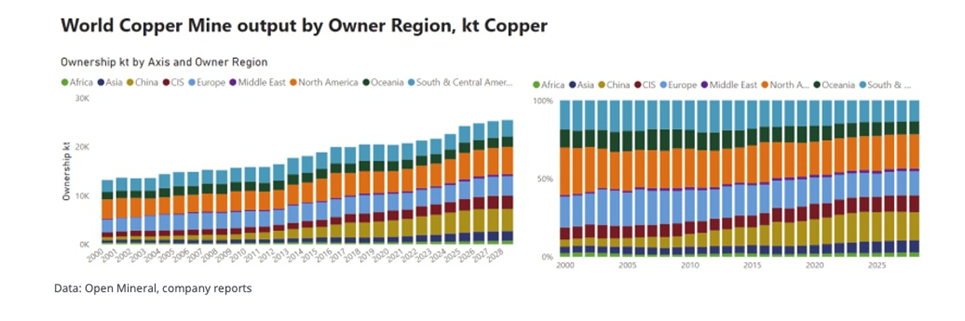

A recent report by Open Mineral studied trends in copper mine ownership. “The most striking takeaway, say the report’s authors, “is that Chinese firms have dramatically increased their equity in global copper mine supply, from 5% at the start of the century to 19% by 2023 following a series of forward-looking investments across the developing districts of the African copper belt and western China, as well as moves into more mature mining regions in South America and Europe.”

“With China’s huge copper smelting capacity and manufacturing base, these investments represent a bold, long-term strategy aimed at securing copper supply for the country’s future.”

“While the volume of mined copper owned by Western majors, mid-tier and junior miners has risen from 8.1Mt in 2000 to just over 10Mt in 2023, the overall share of North America, Europe and Oceania has fallen from over 60% of global copper mined at the start of the century to ~46% last year. Companies from these regions have retreated to some degree from Asia ex-China, while despite key investments their share of African mine output has compressed because a larger proportion of new copper belt supply has been developed by Chinese companies.”

We don’t have to look very hard to show this is the case.

In 2018, China’s largest gold company, Zijin Mining, took over Canada’s Nevsun Resources for $1.4 billion, adding the Timok copper-gold project in Serbia and a 60% stake in Eritrea’s Bisha copper-zinc mine to its asset portfolio.

The same year, Zijin paid $1.26 billion for 63% of Serbia’s largest copper mining and smelting company, RTB Bor.

In Africa, Chinese state-run conglomerate CITIC purchased a 20% stake in Canada’s Ivanhoe Mines (TSX:IVN) for $723 million. The news release says Ivanhoe will use the proceeds to advance its development projects in southern Africa, including Platreef, Kipushis and Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC — the largest copper mine to open recently, in July 2021.

The project is a joint venture between Ivanhoe (39.6%), Zijin Mining (39.6%), Crystal River Global Limited (0.8%) and the DRC government.

Ivanhoe signed two offtake deals, one with a subsidiary of Zijin Mining; the other with Chinese commodities trader CITIC Metal, to sell each 50% of the copper production from Kakula — the first of two mines involved in the joint venture. In other words, 100% of Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production goes to China.

2023 saw China’s MMG agreeing to pay $1.9 billion for Cuprous Capital, a private company that owns the Khoemacau copper mine in Botswana.

Also last year, South Africa’s Sibanye Stillwater (NYSE:SBSW) reportedly planned to bring in a Chinese investor to form a partnership if it won its bid to buy Zambia’s Mopani Copper Mines. The story says Sibanye was competing with Zijin Mining, and that Sibanye’s CEO wanted to diversify into copper from South Africa’s gold and platinum mines, where output has been reduced due to blackouts and rising crime.

In the end it was International Resources Holding RSC of Abu Dhabi that won the bid and will invest $1.1 billion in the previously Glencore-owned mine.

The latest Chinese copper acquisition again involved Zijin Mining, which in January of this year said it plans to take a 15% stake in Canadian copper company Solaris Resources (TSX:SLS). According to the Financial Post, the $130 million investment would be used to advance Solaris’ Warintza copper project in Ecuador.

The majors

The biggest copper merger to surface among the major miners was BHP’s attempted take-over of rival Anglo American.

The $39 billion acquisition was centered around Anglo’s South American copper assets, but BHP walked away after Anglo rejected a last-ditch attempt for more time, Reuters said. The main reason for the deal’s collapse was the requirement that Anglo unbundle its South African platinum and iron ore businesses. Mining.com noted that a tie-up would have given BHP about 10% of global copper production.

The mining giant is certainly ambitious in its pursuit of copper. In April 2023 an Australian court approved its $6.4 billion takeover of OZ Minerals, which at the time was the company’s biggest M&A transaction since its $12.1B purchase of Petrohawk Energy in 2011.

OZ owned two operating copper and gold mines in South Australia, Carrapateena and Prominent Hill, as well as the West Musgrave nickel and copper project in Western Australia.

Late last year, another blockbuster copper buy-out plan made headlines. This time it was Glencore’s (LSE:GLEN) $22.5B bid for Canada’s largest diversified miner, Teck Resources (TSX:TECK). After much back and forth, Glencore agreed to spend $6.93 billion for Teck’s metallurgical coal division, and merge it with its own coal assets — leaving Teck’s copper assets intact. The owner of the Highland Valley copper mine in British Columbia is also a part owner (with Newmont Mining) of Galore Creek, one of the world’s largest undeveloped copper-gold-silver deposits. Teck also has operations in Peru, Chile and the United States.

The world’s second-largest miner, Rio Tinto (LSE:RIO), is investing in copper mines in Utah and Arizona. In 2017 Rio committed an additional $302 million to the Resolution copper project. To date, partners Rio Tinto (55%) and BHP (45%) have spent over $2 billion to develop the stalled project, which has been in the permitting phase since 2013.

The company in 2023 said it intends to invest about $920 million at its Kennecott copper operations in Utah as part of a plan to increase its copper supply in North America.

Of course we can’t forget about Newmont’s $16.8 billion buyout of Australia’s Newcrest Mining, which also completed in 2023. A cornerstone of the deal was Newmont diversifying from gold into copper, by acquiring Newcrest’s copper assets, including the producing Cadia mine in Australia (17Moz of gold and 3.6Mt of copper in reserve) and the Wafi-Golpu development project in Papua New Guinea. One source said the tie-up doubled Newmont’s copper reserves.

Newcrest in 2019 purchased 70% of the Red Chris copper-gold mine in British Columbia, forming a joint venture with the mine’s owner, Imperial Metals (TSX:III). Newcrest’s 70% share transferred to Newmont when the Newmont-Newcrest deal was finalized.

Through our own research, AOTH identified more copper investments:

- China’s Jiangxi Copper bought 25.9 million First Quantum Minerals’ shares, helping the beleaguered Canadian miner to raise CAD$1.5 billion in February. First Quantum (TSX:FM) in 2023 had its Cobre Panama mine shut down by the government. The Chinese firm, which holds 18.4% of FM, also agreed to buy $500 million in copper shipments from a First Quantum mine in Zambia.

- Russian firm Norilsk Nickel has been forced to close its Arctic copper plant due to Ukraine-related sanctions. Reuters said Norilsk will instead build a new plant in China through a joint venture, with construction slated for completion by mid-2027.

- Lundin Mining (TSX:LUN) in March of last year acquired a majority interest in Chile’s Casserones copper-molybdenum mine. The Toronto-based company paid $800 million for a 51% share of SCM Minera Lumina Copper Chile, a subsidiary of JX Nippon Mining & Metals, which operates the mine. Lundin will also pay JX $150 million in instalments over six years, and have the right to acquire an additional 19% interest by paying $350M over five years.

Smelters

At the top we said that every link in the copper supply chain is wanting metal and worried about not getting enough. This includes copper smelters, which buy the raw ore from mining companies and refine it into finished products, for a fee.

While this appears to be a new trend, in fact it goes as far back as 2010. That year, Dowa Metals & Mining, a unit of Dowa Holdings, Japan’s fourth-largest copper smelter, planned to double the ore procurement rate from its mines to 30% in five years, facing competition from China and India.

“Expansion of China’s smelting capacity has caused an ore shortage that will persist through at least 2014, according to CRU Group. Processing fees slumped 38 percent this year as smelters competed to process scarce raw material,” Bloomberg reported at the time (Sound familiar? The same thing is happening now — Rick)

The news outlet noted that Dowa Holdings, in a venture with Sojitz Corp. and Furakawa Co., said it would spend $183 million to buy a 25% stake in the Gibraltar copper mine in British Columbia from Taseko Mines (TSX:TKO).

Staying with Japan, in 2020 the country’s top smelter, JX Nippon Mining & Metals, increased ownership of its then-majority-held Caserones copper mine in Chile (it is now 51% owned by Lundin). The company bought Mitsui Mining’s 25.8% stake after the cost of the troubled project doubled to $4.2 billion, according to The Northern Miner.

The following year, Mitsui Mining & Smelting offloaded its 0.97% stake in the Collahuasi copper mine in Chile to its parent company, Japanese trading firm Mitsui & Co, Mining Technology said. As mentioned, Anglo American and Glencore each own 44% of the open-pit mine. The remaining 12% is held by Japan Collahuasi Resources (JCR).

In 2018, a Reuters story said “Chinese copper smelters are looking to make more investments in mines, pushing to shore up supply of concentrate at a time when competition for the raw material is heating up, industry executives said. China is the world’s biggest consumer of the metal but its own copper mine production has been stagnating amid a broad crackdown on pollution, exacerbating a heavy reliance on imports.

“More direct tie-ups with mines would diversify smelters’ sources of supply, as well as potentially giving them more sway in annual supply negotiations with large global miners such as BHP and Freeport-McMoRan Inc.”

The article went on to say that a private Chinese smelter, which uses 100% copper concentrate and no scrap, was looking to deal with copper mines directly. It quoted the executive vice president saying the smelter is looking at potential investment in mines in South America, Europe and some African countries with stable political environments.

Getting more current, Japan’s Mitsubishi Materials Corp in 2023 said it aims to more than triple its copper concentrate output through equity holdings by 2030, possibly through buying stakes in early and mid-stage development projects.

The company, which owns stakes in several copper mines including Los Palambres and Mantoverde in Chile, wants to boost its copper concentrate production to 500,000 tonnes a year from 150,000t now. The plan would cost $1.9 billion by the end of the decade, including investments in copper mining and smelting.

Juniors

We found that several majors have been investing in early-stage junior resource companies, who, as I have stated many times before, own the world’s next mines. Among recent transactions:

- Freeport McMoRan (NYSE:FCX), the world’s largest publicly traded copper miner, in 2021 acquired all the shares of Carpo Resources and its Yandera copper project in Papua New Guinea. Measured and indicated resources amount to 6.2 billion pounds of copper equivalent, from resources of almost 8 billion pounds of CuEq.

- Max Resource (TSXV:MAX) cut an 80/20 earn-in deal with Freeport for its Cesar copper-silver project in Colombia. Under the agreement, announced on May 13, Arizona-based Freeport has an option to acquire up to 80% of Cesar by spending CAD$50 million to explore the property.

- In August 2023 Rio Tinto agreed to buy Pan American Silver’s stake in Agua de la Falda S.A., a company with exploration tenements in Chile’s Atacama region, and to a joint venture with Codelco to develop Agua de la Falda’s assets.

Under the agreement, Rio Tinto will acquire Pan American’s (TSX:PAAS) 57.74% operating stake in Agua de la Falda for $45 million and the grant of net smelter returns royalties. Rio Tinto will also acquire the nearby Meridian property for $550,000 and the grant of NSRs.

Codelco, which is the world’s largest copper producer and is owned by the Chilean government, holds the remaining 42.26% of Agua de la Falda.

- Pan American was also involved in a deal with Glencore in July 2023, wherein Glencore bought PAAS’s 56.2% stake in the Mara project, located in the Catamarca province of Argentina. The 27-year copper-gold mine has proven and probable reserves of 5.4 million tonnes of copper and 7.4 million ounces of gold.

- Last year, First Quantum Minerals partnered with Rio Tinto to advance one of the world’s largest undeveloped copper resources, the La Granja copper project in Peru. According to the March 30, 2023 news release, La Granja has an inferred resource of 4.32 billion tonnes at 0.51% copper. Rio Tinto has operated the project since 2006. First Quantum will acquire a majority stake and will undertake the feasibility study.

- In December 2023, Rio Tinto signed a deal with Arizona Sonoran Copper (TSX:ASCU) that could make Nuton, a Rio subsidiary, a partner and de-risk the Cactus project.

The collaboration could earn Nuton a 40% stake in the project on the site of the past-producing Sacaton mine south of Phoenix.

- In February 2024, Midnight Sun Mining (TSXV:MMA) teamed up with privately held KoBold Metals to explore Dumbwa, one of four targets on its Solwezi copper project in Zambia. KoBold will spend $15 million on exploration over the next four years and make cash payments to Midnight Sun of CAD$500,000, to earn a 75% interest in the Dumbwa target.

In April, Midnight Sun and First Quantum Minerals agreed to jointly define potential feed sources at the Solwezi project for First Quantum’s SW/EW oxide copper circuit at its Kansanshi mine.

- Finally, in April 2024 China-focused Silvercorp Metals (TSX:SVM) acquired Adventus Mining (TSXV:ADZN), the rationale being to increase Silvercorp’s exposure to gold, as well as metals key to a low-carbon future, including copper. A news release states that Silvercorp has the technical ability to develop the El Domo copper-gold project in Ecuador into a mine — having built eight mines in its current operations, three flotation mills of similar size to El Domo, and three tailings storage facilities.

Conclusion

The global hunt for copper has been on for decades, at least since the mid-‘90s, but it has been accelerating, as companies involved in all parts of the copper supply chain realize the structural supply deficit facing the copper market. They understand the need to find sources —existing mines, expansions, brownfield projects, greenfield projects, etc. and are making deals to acquire the base metal, which is not only essential to electrification and decarbonization, but industry in general.

Along with the usual applications in construction wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, there is now added demand for copper in electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

EVs use triple the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars. Additional copper is being demanded by the electrification of public transportation systems, 5G and AI.

Yet the 22 million tonnes of copper mined last year isn’t going to meet the required demand, especially as governments continue to set ambitious, some say impossible to meet, emissions reduction targets.

A recent study found that to electrify the global vehicle fleet requires bringing into production 55% more new mines. Between 35 and 195 large new copper mines would have to be built over the next 32 years, at a rate of up to six mines per year. In other words, mission impossible.

Automakers are worried about running out of supply and are going directly to the mines. In August 2023, Stellantis announced it would pay $155 million for a 14.2% stake in McEwen Copper (a subsidiary of Canada’s McEwen Mining (MUX.TO) and its Los Azules project in Arizona.

Some majors are taking the easy way out and buying other majors to top up their copper reserves (none of this activity increases global copper reserves). Examples include BHP’s attempted takeover of Anglo American, Newmont’s acquisition of Newcrest, and Glencore’s failed bid to get Teck and its copper asset portfolio.

Others, like Freeport McMoran (NYSE:FCX) are doing the harder work of acquiring juniors like Max Resource (TSX.V:MAX), the owners of the deposits that might become the next copper mines. As the number of mid-tier and major miners on the selling block is reduced, these major miners moving towards the bottom on the mining food chain and earning into junior held projects, will increasingly become the norm. Juniors own the world’s future mines, they are the ones the few left standing majors will have to buy, or partner with, in order to increase their reserves.

Copper smelters are growing tired of scratching around for copper and receiving a pittance in treatment charges. They too are going directly to the mines to ensure a steady supply of copper feed. So far it’s mostly Japanese companies, but how long before Chinese smelters, responsible for around half of global refined copper production, catch on and do the same?

China smartly began its global project to acquire the most important metals — not just copper but iron ore, lithium, cobalt, graphite, rare earths — and process them domestically decades ago. A run through recent copper M&A shows China continues to see copper as a top priority.

“With China’s huge copper smelting capacity and manufacturing base, these investments represent a bold, long-term strategy aimed at securing copper supply for the country’s future,” reads a recent report.

Western countries would be wise to do the same but I fear it may be too late. Existing mines are becoming depleted, head grades are declining, and the copper discovery cupboard is bare. On top of this we have resource nationalism in some of the big copper-producing countries (Chile, Peru, Panama) ongoing labor disruptions, and climate change crimping production.

I’ll say it again, along with an example of an advanced junior working in a safe jurisdiction, junior mining companies, like British Columbia’s Kodiak Copper (TSX.V:KDK), own the world’s potential future mines.

Every year so-called experts predict a surplus; instead what happens? Deficit after supply deficit.

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI) forecasts global copper consumption to grow 3.5% to 28 million tonnes in 2024, and for demand to increase from 27 million tonnes in 2023 to 38 million tonnes in 2032, averaging 3.9% yearly growth.

Yet the US Geological Survey reports supply from copper mines in 2023 amounted to only 22 million tonnes. If the copper supply doesn’t grow this year, we are looking at a 6Mt deficit.

Our calculations showed the current 22 million tonnes of production reflects roughly a 20% reduction in output from the top 20 copper mines. If supply interruptions continue in some of the top producers, like Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, the deficit could grow even bigger, and likely will.

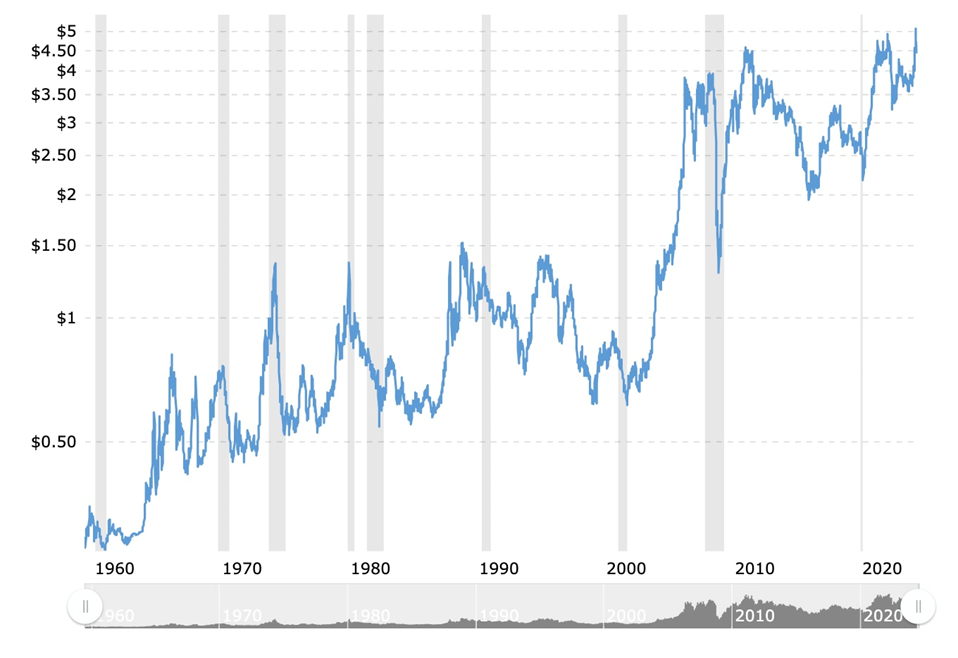

It should now be obvious why everyone is scrambling to get their hands on copper. Once the workhorse of the global economy, cheap and plentiful, copper has been elevated to the world’s critical mineral, with rising prices indicative of over-demand and under-supply.

Source: Macrotrends

Source: Macrotrends

Read the full article here