Peter recently returned to the Mining Network for an interview with Peter Gadsdon. In this interview the duo covers executive overreach, unreliable government jobs data, a weakening dollar, and why persistent inflation will keep the Federal Reserve from cutting rates. Peter ties all of these threads to a larger theme — loss of confidence in fiat money and the growing logic for holding sound money.

He opens by calling out a recent deal struck by President Trump and Nvidia that oversteps constitutional authority and functions like an export tax. Peter sees it as another example of presidential power expanding at the expense of constitutional limits and ordinary commerce:

Trump doesn’t have the authority to do this. And also, it amounts to an export tax, which is completely unconstitutional because the Constitution doesn’t even give the government the power to tax exports. They can tax imports, but those are supposed to originate in the House of Representatives, not with the White House. So Trump is making a mockery of the Constitution. He is dramatically expanding the power of the government, particularly the presidency.

He follows that up by questioning the motives behind a recent politically-motivated firing and connects it to what he sees as a systematic problem with jobs numbers. Peter thinks the administration has been misreading — and taking credit for — data that is often revised substantially after the fact:

The crazy part about the fact that he fired her was why. He didn’t fire her because all six of the last jobs numbers have been wrong, right, because everyone was revised way down. Meanwhile, every time one of these jobs reports came out better than expected, Trump was taking credit, even though we now know that every single jobs report that he took credit for wasn’t a beat, but it was a miss. In fact, the last two reports were revised down by the most in 50 years. So the job creation record so far on Trump’s watch has been dismal.

From domestic statistics he moves to international consequences. Peter warns that if the United States keeps treating its fiscal position as flexible — relying on inflation to erode real debt burdens — foreign holders of dollars and government debt will lose faith and reduce their holdings. He expects this to accelerate a shift away from the dollar and into hard assets:

Well, I mean, I think there’s a loss of confidence in the dollar and in the fiscal integrity of the United States. I think it should be clear to our creditors that we’re never going to get our house in order, that we’re going to inflate away any debt obligations that they’re foolish enough to hold onto. So I think the de-dollarization trend is going to continue and accelerate. I think central banks will keep the investing of dollars and moving more and more of their reserves into gold. I think the world will continue to wean itself off of the US dollar for global payments and transactions.

He also explains why attempts to lower the government’s interest burden by leaning on short-term borrowing are dangerous. Borrowing at the short end only helps if long-term yields cooperate; if they rise, the strategy can leave the country exposed to refinancing risk and sudden increases in interest costs:

The US would only save that money if they do all the borrowing at the very short end of the curve. Because if I’m right and the Fed cuts rates and the yield on long-term bonds goes up, that doesn’t help the government. Right? So the only way the government would save money would be to keep borrowing real short. But that is in a very risky position to put the country in.

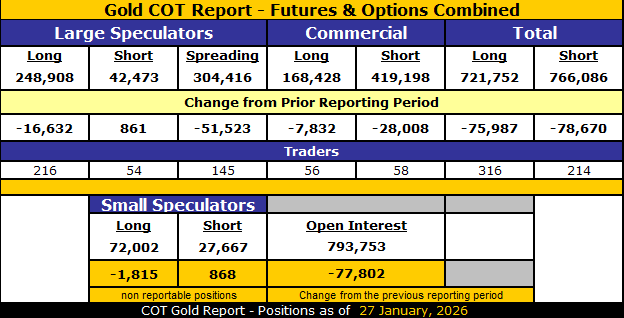

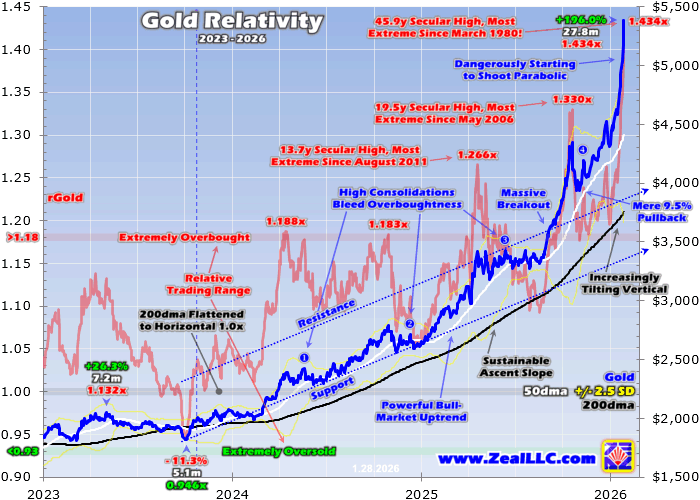

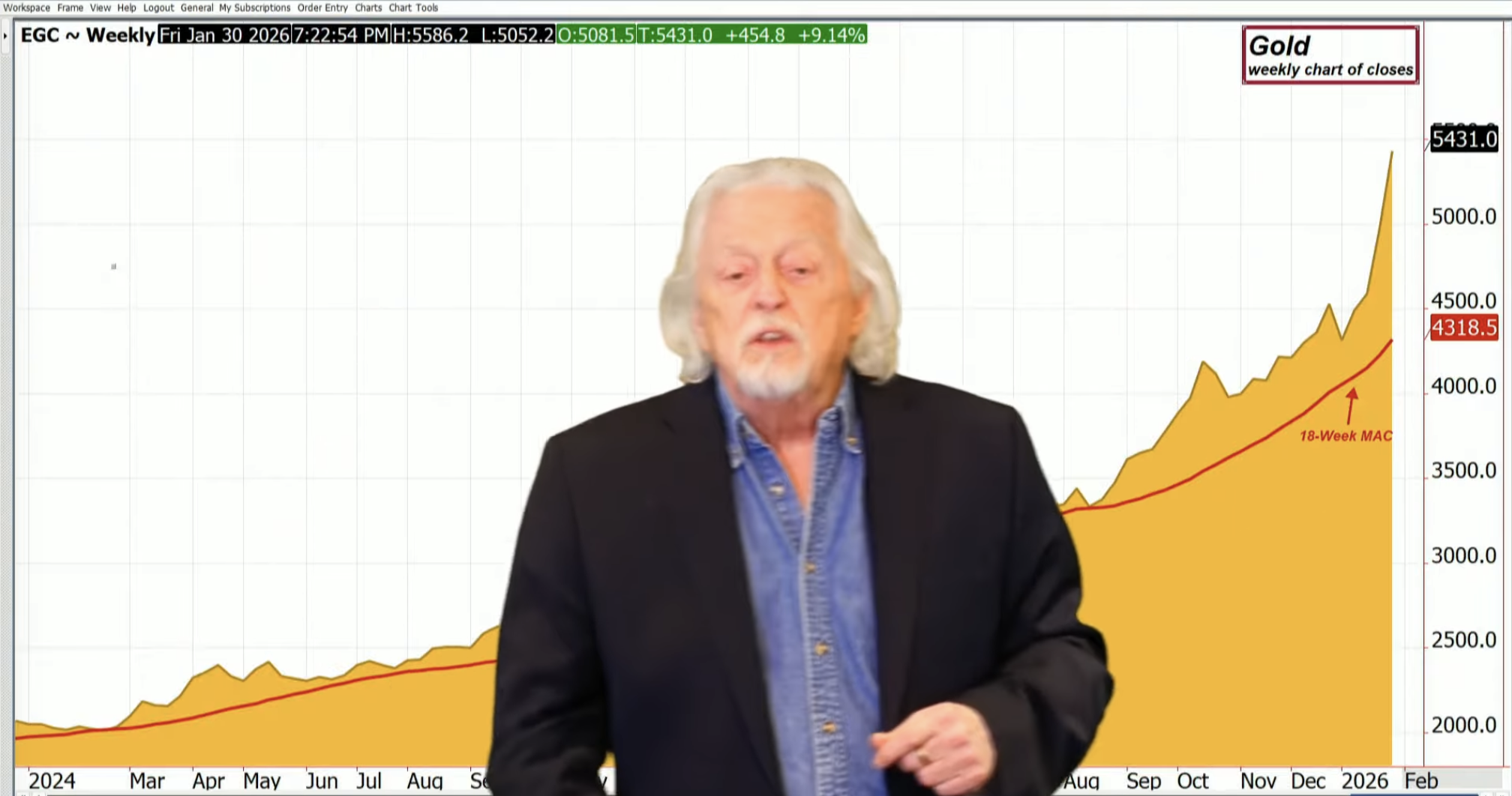

Finally, Peter turns to gold markets and the distinction between paper claims and physical metal. He warns that much of the activity in gold is speculative — futures are rolled rather than delivered — but a real run for physical metal could expose the limits of that paper market and create a squeeze. That, in his view, is precisely the kind of event that reveals the value of holding real, deliverable assets rather than promises:

But I do believe that eventually there could be a run on the futures markets because normally people are buying gold futures. They don’t need the gold and they don’t want the gold. They’re just trying to bet on the direction of the gold. They’re happy to roll over the contract to the next month as the contracts mature because they don’t actually need the gold. … Maybe you get the COMEX going bankrupt if the COMEX stands behind all these commitments that the shorts have made.

If you missed it, be sure to check out Peter’s latest podcast!

Call 1-888-GOLD-160 and speak with a Precious Metals Specialist today!

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply