Distress in the commercial real estate bond market is at all-time highs, a sign that the Fed has messed up the economy more than most people realize.

Most mainstream commentators are sanguine about the economy. They believe the Federal Reserve has effectively reined in price inflation and expect a “soft landing” as the central bank eases monetary policy.

But there are cracks in the economic foundation caused by more than a decade of artificially low interest rates and multiple rounds of quantitative easing. The Federal Reserve addicted the country to easy money. Practically speaking, it incentivized excessive borrowing and created all kinds of malinvestments in the economy.

When the Fed suddenly and aggressively raised interest rates to fight price inflation, it exacerbated the problems it had already caused. We saw that manifest in a banking crisis that the Fed managed to paper over with a bailout.

Where problems will surface next remains to be seen, but the commercial real estate (CRE) sector is a prime candidate.

The CRE sector faces the triple whammy of falling prices, falling demand, and rising interest rates. The post-pandemic rise of telecommuting and work-at-home programs crushed demand for office space. Government lockdowns crushed the retail sector. Vacancy rates in commercial buildings have soared. This has put significant stress on commercial real estate companies. The biggest bankruptcy in 2023 was the failure of the Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust. The company had loaded up with more than $1 billion in liabilities.

The U.S. has the biggest commercial real estate market in the world. According to the IMF, as of January, commercial real estate prices had tumbled by 11 percent since the Fed started hiking rates in 2022. This precipitous drop in commercial real estate value erased the previous two year’s gains.

Despite a 50 basis rate cut in September and another quarter-point of easing in November, the CRE sector remains under stress. We can see this stress manifested in the Commercial Real Estate Collateralized Loan Obligation (CRE-CLO) bond market.

CRE-CLO bonds are backed by a pool of loans secured by commercial properties, such as office buildings, retail centers, industrial properties, hotels, and multifamily housing. CRE-CLOs are generally shorter-term bridge loans used to refinance commercial real estate properties or fund new acquisitions and feature floating interest rates.

Financial analyst Artis Shepherd noted that bridge loans of this nature were recently, and most notably, used to facilitate the biggest apartment investment bubble in history.

At the end of Q3, the distress rate for CRE-CLO loans across all commercial real estate sectors reached an all-time high of 13.1 percent. “Distress” is defined as any loan reported 30 days delinquent or more, loans past their maturity date, loans in special servicing (typically due to a drop in occupancy or a failure to meet certain performance criteria), or any combination thereof.

Many of the loans held in current CRE-CLO bonds originated between 2020 and 2022 when rates were still near zero and commercial real estate prices were peaking. Given their maturities were three to five years, many of these loans are close to coming due. As Shepherd put it, “A wall of maturities is staring borrowers, lenders, and bondholders in the face, all while underlying property performance disappoints.”

“Despite attempts by lenders to extend and pretend—kicking the can down the road in the short term to avoid defaults until the Federal Reserve lowers rates enough to bail them out—their delusions of reprieve may be fading fast.”

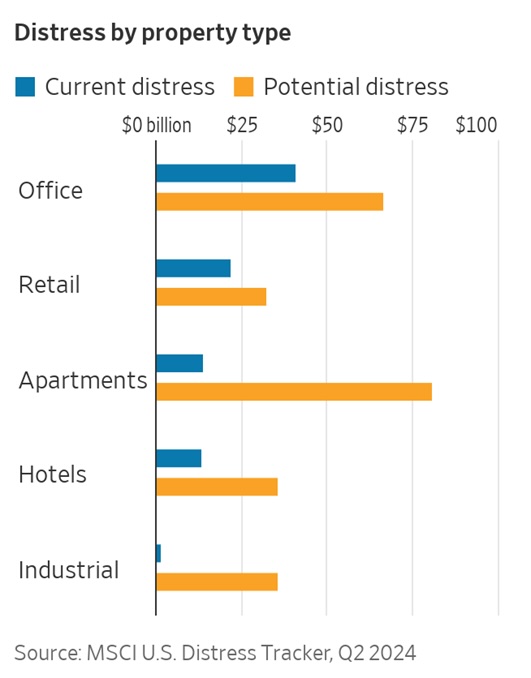

Office properties are feeling the tightest squeeze, with 20 percent of CRE-CLO office loans characterized as distressed. Stress is also high in the retail property sector.

Shepherd said the real story is in the multifamily dwelling sector.

“The distress rate for apartments touched 16.4 percent in August. An astonishing number, indicating that one in six apartment bridge loans were distressed. The improvement to 13.7 percent shown for September is seasonal, as renters settle in at the start of the school year.”

According to a Wall Street Journal report using data through the first half of 2024, the batch of currently distressed apartment bridge loans totaled $14 billion. Even more troubling, there were an additional $81 billion in potentially distressed loans.

Shepherd ran the math and came up with a startling revelation.

“The arithmetically-aware will note that if the $14 billion of currently distressed apartment bridge loans comprise a roughly 14 percent distress rate at the end of Q2 (as shown in Figure 1) and there are an additional $81 billion in potentially distressed loans not yet categorized as ‘currently distressed’ (as shown in Figure 2), then MSCI data implies that 95 percent of all apartment bridge loans are either currently distressed or in imminent danger of distress.”

Shepherd noted how Fed policy incentivized reckless loan writing.

“In the 2020-22 period, bridge loans of this variety were ubiquitous above a certain minimum loan size. And, because of the extreme and reckless nature of money printing undertaken by the Federal Reserve during this time—when interest rates were effectively zero—lenders underwrote property acquisitions with a 1.0x debt service coverage ratio (“DSCR”), meaning the initial net operating income of the property was projected to just cover interest payments, with nothing left over.”

The gamble paid off while rates were low. But Federal Reserve rate hikes to fight price inflation changed the playing field.

Bridge loan interest rates were in the 3.5 percent range until mid-2022. As Shepherd notes, a property acquired during this period with a net operating income of $1 million would have also had interest payments of $1 million at the then-prevailing interest rate.

Today, rates have soared to 8.4 percent. You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in math to see the problem. The interest payment on that same property has more than doubled to $2.4 million.

This is yet another reason people are clamoring for rate cuts even though there are plenty of indications that price inflation isn’t dead and buried.

This underscores the problem facing the Federal Reserve. It needs to drive rates lower to keep the problems it caused by more than a decade of easy money from blowing up in its face, but it also needs to hold rates higher for longer to keep that pesky inflation at bay.

It seems like an impossible balancing act.

The collapse of the commercial real estate market could easily spill over into the financial sector.

According to data from the Mortgage Bankers Association, as of the end of 2023, around $1.2 trillion of commercial real estate debt in the United States was set to mature over the next two years.

According to Trepp (a real estate data provider), $2.56 trillion in commercial real estate loans will mature over the next five years, with $1.4 trillion held by banks.

All of that debt will have to be refinanced. That’s a big problem for debtors who face much higher interest rates to borrow money on buildings with much lower values.

Small and midsized regional banks hold a significant share of commercial real estate debt. They carry more than 4.4 times the exposure to CRE loans than major “too big to fail” banks. According to an analysis by Citigroup, regional and local banks hold 70 percent of all commercial real estate loans. And according to a report by a Goldman Sachs economist, banks with less than $250 billion in assets hold more than 80 percent of commercial real estate loans.

The IMF summarized the situation.

“Financial intermediaries and investors with a significant exposure to commercial real estate face heightened asset quality risks. Smaller and regional U.S. banks are particularly vulnerable as they are almost five times more exposed to the sector than larger banks. … Rising delinquencies and defaults in the sector could restrict lending and trigger a vicious cycle of tighter funding conditions, falling commercial property prices, and losses for financial intermediaries with adverse spillovers to the rest of the economy.”

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply