One thing I have not predicted for 2024 is stock-market crash, and so far I haven’t predicted one for 2025 either. However, Adam Taggart’s guest in a video posted below says he anticipates a huge market crash is coming soon.

You certainly wouldn’t know it to look at the market today, where both the Nasdaq and S&P continued barreling upward, topping recent records. It looks like Santa Clause is firing up his sleigh to get ready for his post-Christmas run. AI server manufacturer Super Micro Computer led the climb with a bright-red nose, surging nearly 29%. That said, I lean the direction of Taggart’s guest, though I’m not making any predictions at this point.

One thing that has been surprising to me is to see how slow the crash of the Everything Bubble is going. It’s still going, and I always said it would play out over years, not months; but sometimes it just seems to be dragging on without picking up speed. Things are still proceeding in the direction I laid out as a result of Fed tightening, including particularly inflation as the dragon that would not let the Fed off the hook.

Given the sense of dragging time, I want to look at what I started saying five years ago the crash of the Everything Bubble would bring once it began in order to see how that is going.

One thing I have been sure of in my predicting is that the Fed’s battle with inflation is not as over as most people seem to believe it is. Inflation rose at the start of the year when I warned last year we’d see it rise, and then I doubled down on that for the latter part of this year, even though, again, nearly everyone was leaning in the opposite direction when I started saying it, particularly in the mainstream media.

The accuracy of those inflation predictions for a second rise this year, to start around the end of summer, we can see fairly well in today’s headlines as one economist describes how core inflation is rising in spite of falling gasoline prices. The biggest moves in the wrong direction for the Fed’s plans (and for the rest of us who have to live with it) are in core services, which is where inflation has gotten stuck fast for some time. Prices are up 4.4% on an annualized basis. Durable goods also rose for the second month in a row. This all has the Fed talking down the pace of rate cuts it had earlier been talking up.

The major parts of the crash of the Everything Bubble that I predicted we would see have been slow in developing, though they are continually moving in the direction I laid out. It seems fitting, therefore, to take stock in the final month of the year. Here is where the major elements of the Everything Bubble Bust stand (to the extent I have time to write about today. Maybe I’ll go deeper in my next Deeper Dive, depending on what else transpires this week):

The big bond bubble bust

The big trouble in the bond market is coming from commercial real estate where those old mortgage-backed securities are suddenly collapsing at a good clip like they did during the Great Recession, only worse in some ways:

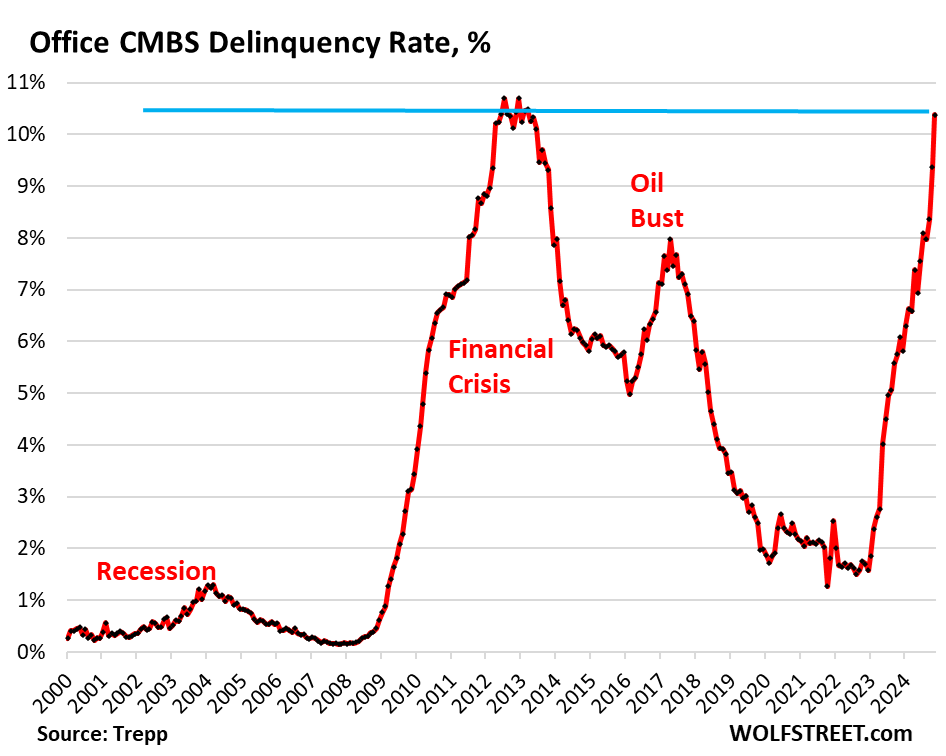

The delinquency rate of office mortgages that have been securitized into commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) spiked by a full percentage point in November for the second month in a row, to 10.4%, now just a hair below the worst months during the Financial Crisis meltdown, when office CMBS delinquency rates peaked at 10.7%, according to data by Trepp, which tracks and analyzes CMBS.

Over the past two years, the delinquency rate for office CMBS has spiked by 8.8 percentage points, far faster than even the worst two-year period during the Financial Crisis (+6.3 percentage points in the two years through November 2010).

The office sector of commercial real estate has entered a depression, and despite pronouncements earlier this year by big CRE players that office has hit bottom, we get another wakeup call:

Just look at the size of the most recent spike in office bond failures:

It’s now a straight-up rocket ride. This dizzying upward acceleration, which is reaching for the moon by past comparisons, has to be making the holders of those CMBS a little nervous. This is a total bond meltdown for this sector:

Amid historic vacancy rates in office buildings across the country, more and more landlords have stopped making interest payments on their mortgages because they don’t collect enough in rents to pay interest and other costs, and they can’t refinance maturing loans because the building doesn’t generate enough in rents to cover interest and other costs, and they cannot get out from under it because prices of older office towers collapsed by 50%, 60%, 70%, or more, and with some office towers becoming worthless and the property going for just land value….

Loans are pulled off the delinquency list when the interest gets paid, or when the loan is resolved through a foreclosure sale, generally involving big losses for the CMBS holders, or if a deal gets worked out between landlord and the special servicer that represents the CMBS holders, such as the mortgage being restructured or modified and extended. And there has been a lot of extend-and-pretend this year, which has the effect of dragging the problem into 2025 and 2026.

Extend-and-pretend can only take you so far, and still involves substantial write-downs. “Survive till ’25” isn’t going to have as much ring to it as it devolves into figuring out how to survive until ’26. You can come up with any new slogan you want, but it’s going to be dead on arrival once it’s clear that “survive till ’25” didn’t do the job.

The hope for ’25 was that the Fed would be fiercely cutting interest rates, which would completely change the math; but with inflation holding the Fed’s feet to the fire and Fed talk of new rate cuts subsiding, there is not a lot of realistic hope to come. Holders of CMBS may already be deep-sixed by ’26. There is no chance the Fed could ever cut interest rates enough to save these zombies anyway. And zombies that can’t even service their debt were a big part of the collapse of the Everything Bubble that I described.

Offices, lodging, retail space and even multi-family buildings are all falling into this hole. The whole change in the way we work that came about because of the Covidcrisis when people sought and experienced other ways of doing things isn’t going away, so there is no hope for office buildings. It’s a demographic change that is caving in these markets.

Another housing market collapse

This one is actually going at the speed I said we’d see clear back when I started writing special posts about the coming collapse for paying subscribers of the Great Recession Blog because I always said the collapse of the housing market would not likely be the big contributor to our downfall that it was back in 2008. It wouldn’t likely go down as far and certainly not as quickly; so that it would follow our decent into economic hell this time around, not lead it.

It was inevitable that housing prices would fall when the Fed raised interest as much as it had to to fight inflation, but homeowners would likely hold out as long as they possibly could to resist the decline of their major asset, and the fall would not become the swift implosion it turned into last time, which happened due to so many adjustable-rate mortgages going off like time bombs during the period of rising rates.

And that is what we are seeing. When the Fed started raising rates, the housing market froze over solid, so declines in prices are still barely being seen, but the ice dam that has held up the flow has recently been showing signs of giving way a little. The key to understanding the difference was that there were very few ARMs this time around the cycle. When I predicted the housing-bubble bust of 2008, it was entirely due to the fact that an enormous portion of the market rested on ARMS that would never withstand a rise in interest rates on such high mortgage balances. Even if the Fed did not raise rates, the loans all had built-in escalation clauses. So rates were set to rise regardless, and homeowners could not refinance their way out either because falling prices meant falling equity, making refis almost impossible.

The housing landscape is now starting to slide away in slow motion:

Big homebuilders cannot sit out this market, they have to do what it takes to build and sell homes to keep their businesses intact and keep their shares from tanking. So they’re building at lower price points, buying down mortgage rates, and throwing in other incentives at a substantial expense to them. Though that may not have been enough.

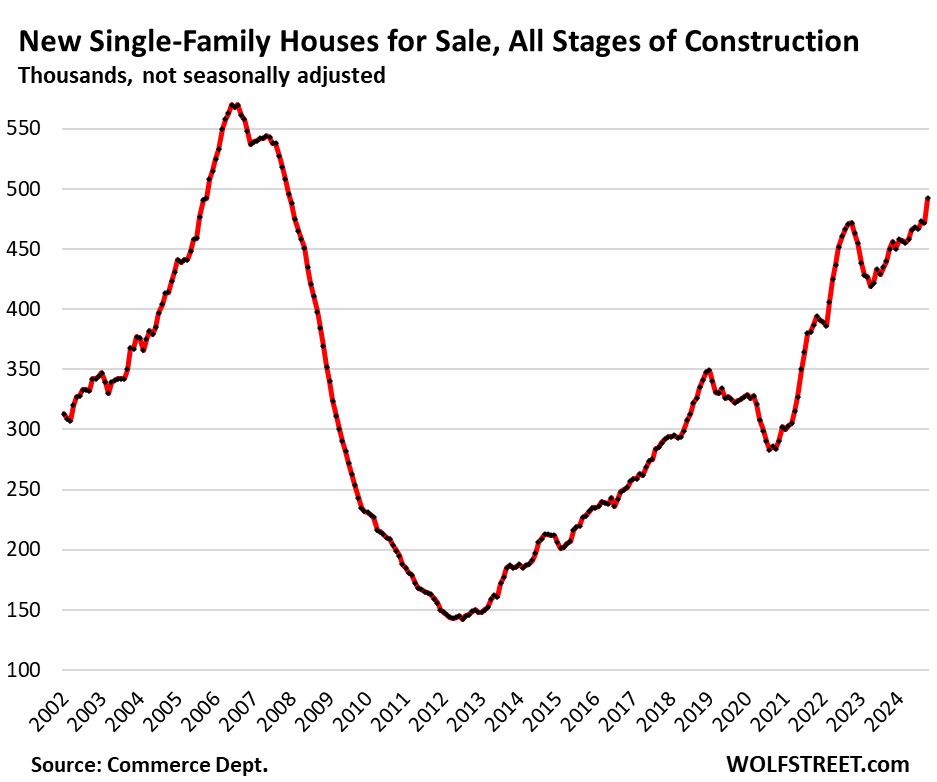

The inventory of new homes on the market has been climbing for a long time, but at today’s still-high prices few are buying, so inventory is now building more quickly;

Almost straight up last quarter because sales of homes plunged in spite of all those builder incentives that were offered at the cost of profits in order to get homes to sell. As for existing houses …

sales have plunged to the lowest levels since 1995 because their too-high prices have triggered large-scale demand destruction. But inventories of new houses have been piling up, and then there’s this sales issue in October with spec houses.

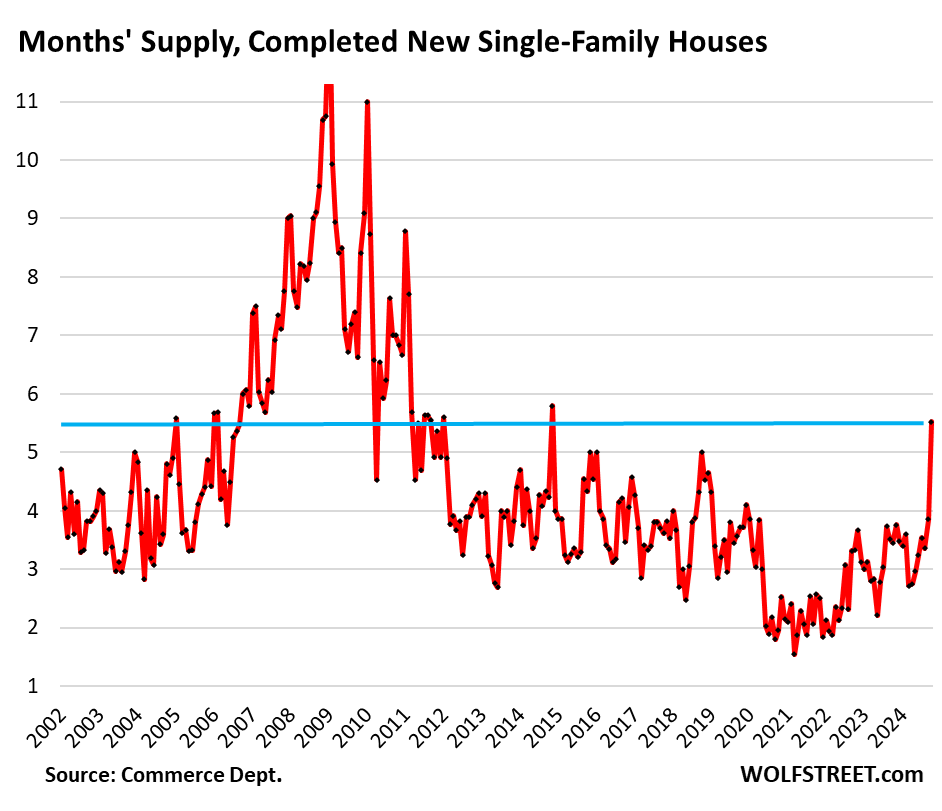

The thing about new homes is that builders cannot hold out when inventory stops selling like homeowners of existing homes often can. They have to start selling at a loss, if necessary, because they start losing money on the interest they have to pay on construction loans. So, there is more incentive to drop prices more quickly or offer even more incentives, but I strongly suspect their ability to raise incentives even more than they have has come to an end.

Since builders have tied up a lot of capital in spec houses, they have to sell them quickly. Rising inventory of completed houses encourages builders to lower prices and offer deals, which will help resolve the mindboggling dislocations in prices that we’ve seen across the housing market.

Sales of completed houses plunged 25% month-to-month in October…. If this doesn’t reverse over the next few months, homebuilders will need to start some serious price cutting to get their inventory moving. Year-over-year, sales fell by 4.5%.

So, the ice dam in new homes appears ready to break.

The walking dead are still walking

The big bust that has been slower to develop into anything horrendous has been the collapse of zombie corporations that aren’t caught up in the real-estate crash. That has happened slowly enough that the stock market has absorbed it without trouble. While I said the stock market would crash in ’22, and it did, I did not say it would crash in ’23 or ’24, and it did not. So, we’re safe on that one, but I would say the collapse of zombie corporations is still underperforming my predictions.

That doesn’t mean we haven’t seen a lot of it with restaurants and retail businesses failing altogether or downsizing. It is certainly moving in the direction I said five years back we’d see develop in the years to come; but so far we are absorbing it without a crisis.

We did, of course, have a big banking crisis bailout in ’23 where banks would have failed much worse due to troubles among zombie tech companies that couldn’t pay their bills once interest rates started rising because they never turned a real profit and were in no shape to refi at higher interest rates. And banks were in no shape to cover the losses and the runs on the bank that resulted because their reserves had been so devalued by the Fed to where, if their reserves had to actually be used, the banks were in big trouble.

That, too, was a foreseen aspect of the Fed’s quantitative tightening that I talked about a few times in my writings. It was inevitable that zombie companies would fail on rate increases, and that would have become far worse if not for the Fed’s huge and rapid bailout of banks that were in hard shape. So, we got away with four headlining bank busts.

In all, the collapse of those banks as the zombies went down was not as large as I predicted, but that was due to the bailouts, which happened because the bust was going to be big without it. So, the lack of bank failures was not because the swelling company failures were small or because bank failures were not formidable.

I don’t think we’ve seen the end of that yet, anyway. I think we may even see more trouble emerge from those reserves at the end of this year; but worse trouble will come if the Fed has to pivot back to raising rates because inflation rises enough that merely stopping its rate cuts is not enough.

Future bubble trouble

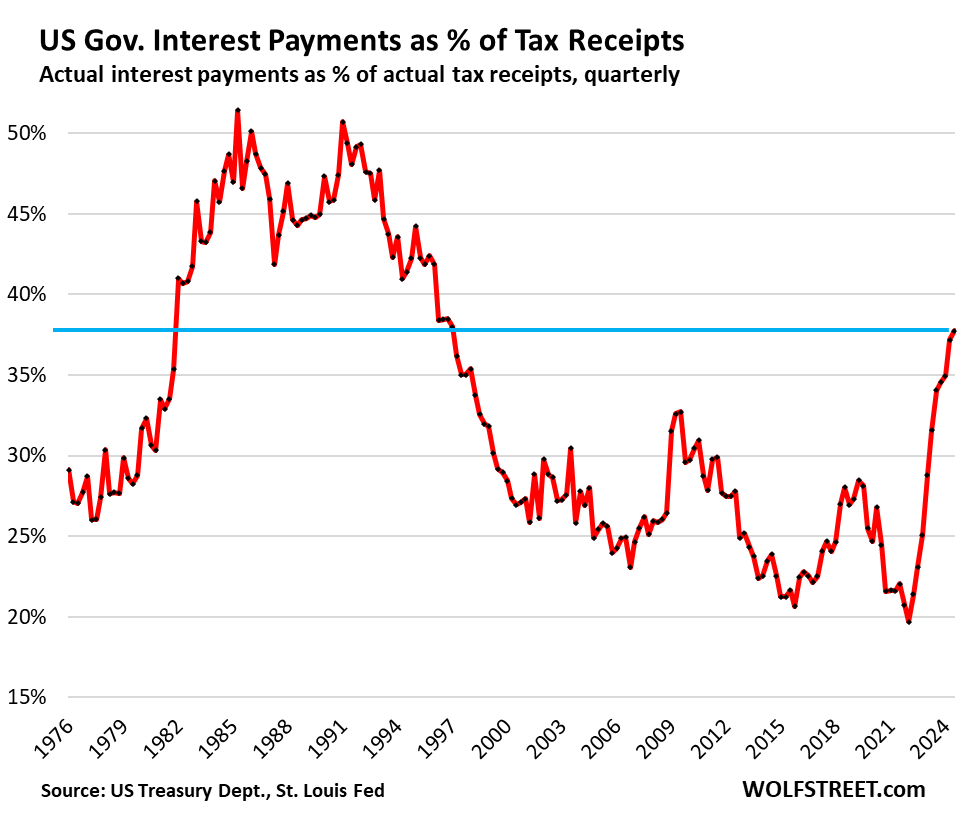

Which brings up this fun little picture of where the US is headed for trouble if interest rates do have to rise again to fight inflation:

It took one year for interest on the US debt, relative to tax revenues, to climb all the way back up to where it was in 1997 when we were coming off the last much-higher interest period of inflation fighting. (Let me remind you that the two peaks in that graph relate to two peaks of Fed-raised high interest as the Fed fought inflation. The second peak happened because the Fed quit tightening too early and, so, had to do it all over again.) After a quarter century of generally lowering interest rates, we’re right back to climbing that mountain peak for interest payments in just one year, even after the Fed’s return to lowering rates.

The magnitude and speed of this spike is unprecedented in modern US history. It does not look good.

Read the full article here