Rain can be either refreshing or destructive. It can make plants grow or produce devastating floods. But in all cases, it’s largely outside human control. Or is it?

True, we have little control over whether rain will fall. We have a lot of control over how it affects us, though. Sturdy homes and good infrastructure can keep us safe and let us enjoy rainfall’s benefits.

Last week in my 2025 forecast letter, I predicted A Partly Cloudy Year, generally mild but with occasional storms. Today we’ll talk about the second half of that sentence. What could go wrong and lead to a worse-than-expected year? In short, what are the main risks to my forecast?

The biggest risk, in my view, is that persistently higher interest rates could do serious damage to both the government’s fiscal outlook and economic growth prospects.

Typically, as we will see, when the Fed starts cutting rates at the short end, the long end of the curve responds by also going down. The bond market seems to be reacting differently this time. We should note what’s happening—and why it’s happening.

The Time Came, and Went

Let’s examine the setup that brought us here. In September, the Federal Reserve began cutting rates. Inflation was not yet at the Fed’s 2% target, but officials believed it was headed that way.

On the negative side, the unemployment rate had crossed above 4% in May and kept rising to 4.2%. The “Sahm Rule” recession indicator had triggered, and other data seemed to be weakening, too. Given all that, it wasn’t crazy to think the Fed should “do something.”

Jerome Powell left no doubt in his Jackson Hole speech, saying “The time has come for policy to adjust.” I said at the time everyone should also note his next sentence: “The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.”

In Powell’s view, the direction was clear. The pace was not. And sure enough, in December the FOMC decided to slow its pace, keeping rates steady and issuing dot plots that dialed back expectations.

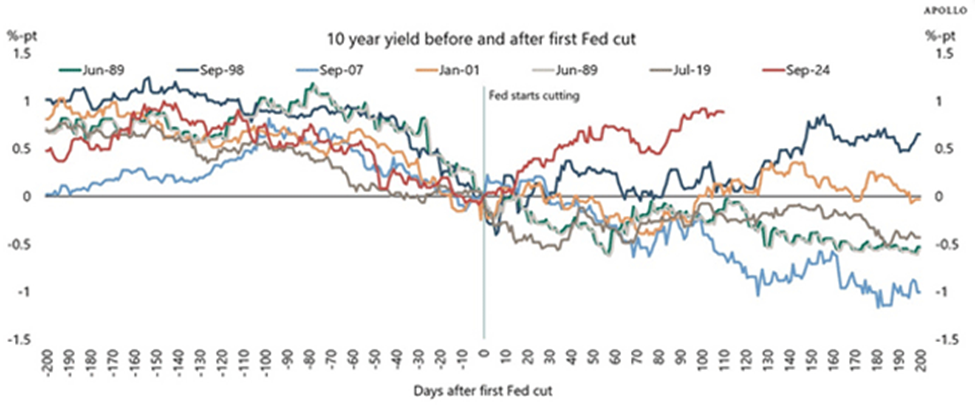

It had probably not escaped the FOMC’s notice that the bond market wasn’t reacting as it had in past cycles. Torsten Sløk showed how in the spaghetti-like chart below.

Source: Apollo

The lines show 10-year Treasury yield before and after the last seven rate cutting cycles. It’s messy but you can see the general pattern: Long-term rates began falling months before the Fed started loosening, then flattened or kept falling afterward.

The red line shows the latest cycle behaving differently. Long-term rates didn’t just rise; they turned on a dime almost as soon as the Fed acted in September. Correlation isn’t causation, as they say, but this sure looks like a reaction to the policy shift. But that begs the question why and what the reaction really means?

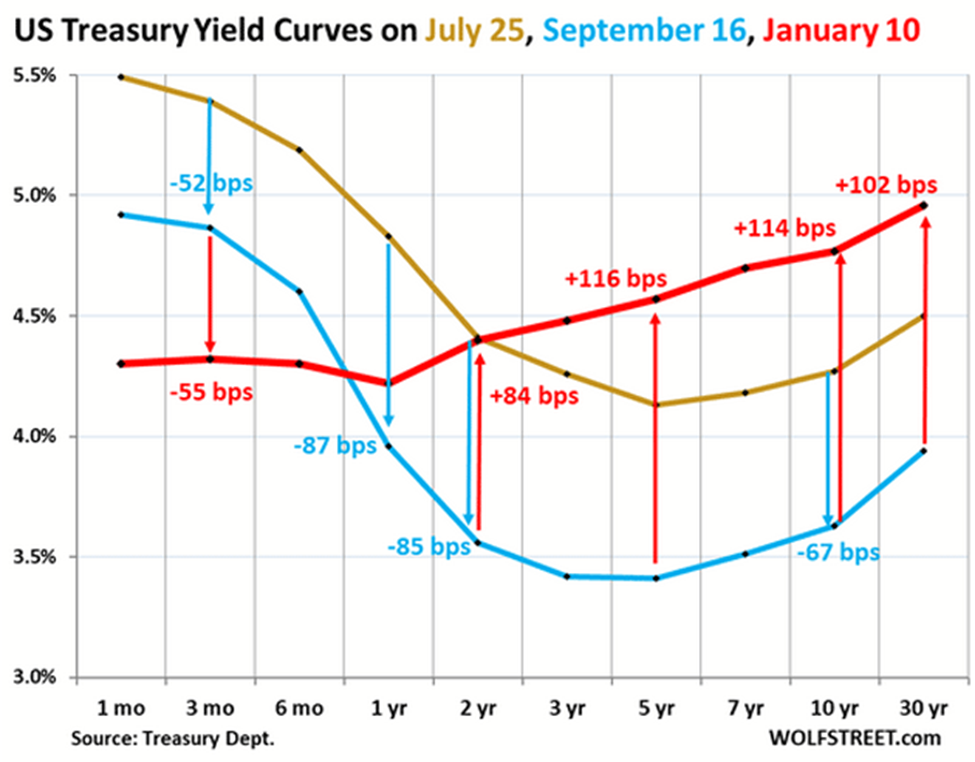

Higher long-term rates are helping restore the yield curve to its normal upward slope. You can see that process unfolding in this Wolf Richter chart.

Source: Wolf Richter

Before the Fed acted (yellow line), the yield curve was still inverted as it had been since mid-2022. The first cut of 50 basis points shifted the whole curve downward by about that amount (blue line). The combination of lower short-term rates and higher long-term rates subsequently produced the current gentle upward slope (red line).

The normal pattern would be for the yield curve to steepen because the Fed is reducing the short end. A concurrent rise at the long end is unusual. And it’s not small. Rates are much higher than they were in July for maturities longer than two years—as much as 116 bps higher for five-year debt. At the longest end, 30-year bond yields are up a full percentage point.

Mortgage and other kinds of private debt typically follow Treasury yields, so this isn’t what the Fed should want to see, if its goal is to delay or at least soften an economic downturn.

Ideally, the inverted yield curve would normalize by the Fed cutting short-term rates faster than the market reduces long-term rates. That isn’t happening this time. Why?

I can imagine several answers to that question, none of them good. But one in particular stands out.

Cue the Vigilantes

As you probably know, my macro thesis is that an excessive government debt crisis will force a global financial crisis—not just in the US but everywhere. Most developed countries have excessive government debt, so the crisis could begin elsewhere, eventually reaching US shores. It wouldn’t be the first time.

The crisis will happen when bond investors decide government bonds are too risky to buy at a yield governments are willing to pay. My expectation has been this will occur in the late 2020s.

Now it’s 2025. Are we seeing the initial signs of this reckoning? It would not be the first instance of my timing being off!

Try to think like a lender. If you’re going to underwrite a long-term loan, you want assurance the borrower will be able to repay—not just now, but for the entire term of the loan. Uncertainties grow with time, which is why rates are generally higher as the loan term gets longer.

Government debt is different, of course, since governments issue currencies and control legal systems. But the general principle still applies. A borrower whose debt is growing faster than their ability to repay is rightly considered riskier and must pay higher rates.

The critical point is that governments can issue currencies. However, history has shown that issuing too much of the currency can create inflation. That means the dollars that will be paid back will not be worth as much as the dollars that were lent in terms of buying power. That is why lenders would want higher rates, to maintain their buying power.

Typically, the world’s reserve currency—the US dollar—has given the US a special privilege of not being held to the same standard as others. We can get away with issuing more dollars. And the world wants them as they keep buying our products and services and stocks and assets.

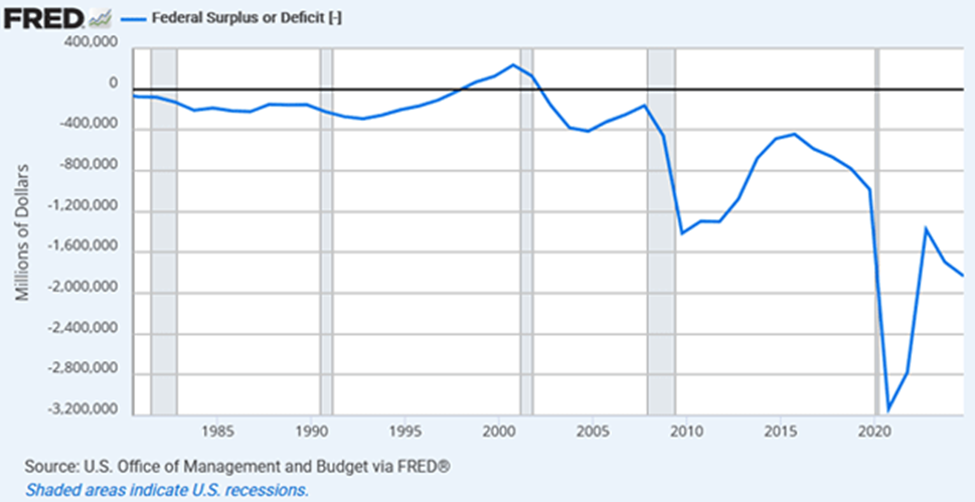

With that in mind, let’s think about the US Treasury’s risk profile. Here is the federal deficit by fiscal year since 1980.

Source: FRED

On the right side we can see how the deficit exploded in 2020. Spending vastly exceeded revenue, thanks to aggressive COVID stimulus programs necessitated by government lockdowns. Some of them proved excessive in hindsight, but at the time seemed necessary. The deficit began improving almost immediately, with 2021 and 2022 looking much better. But then in 2023 and 2024, the progress reversed. Deficits began rising again. Some of this was higher spending and some due to higher interest rates. But regardless, it isn’t what lenders like to see.

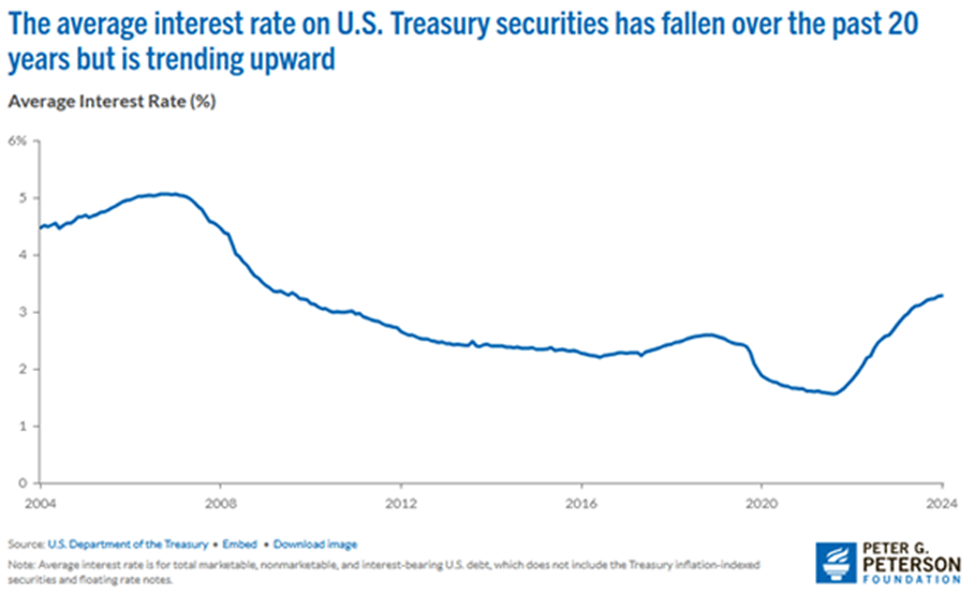

You can see the effect of rising rates in this chart from the Peterson Foundation. The Treasury’s average rate reached a low point in early 2022, just before the Fed began hiking. A year later it was higher than the pre-COVID level, and by mid-2024 was at the highest level since 2010. It’s declined a bit since then (not shown on this chart) but remains high.

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation

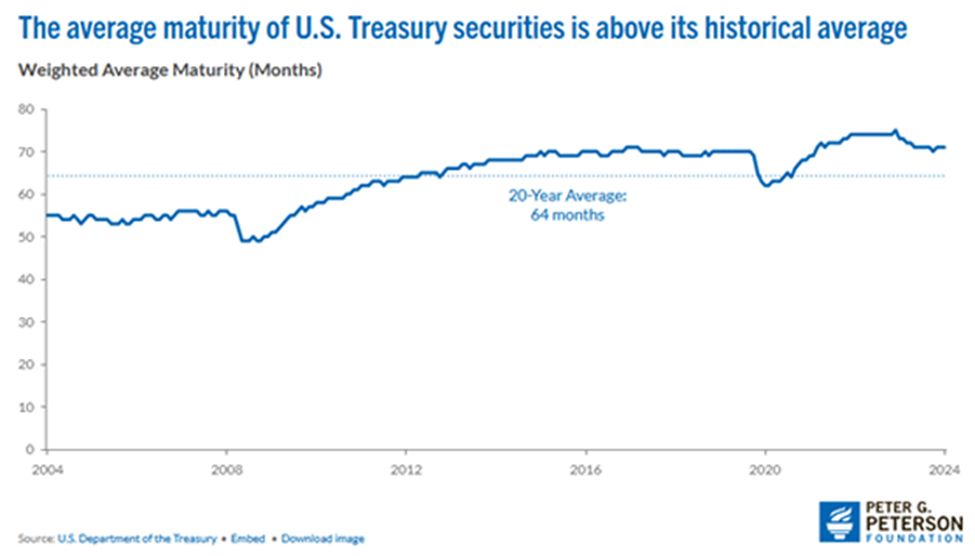

Now, let’s look at the term of the Treasury’s debt.

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation

Since 2004, the Treasury’s weighted average maturity has been around five years. Now it’s more like six years. This is a policy choice, not an accident. The Treasury has to pay the government’s bills and, since tax revenue is never enough, it borrows to cover the difference. But it can choose whether to issue 3-month bills, 30-year bonds, or something in between. [As I said last week, I think Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made what is probably one of the worst decisions since Alexander Hamilton by not issuing many longer-term bonds (20- and 30-year or more?) at rates that we will never see again in our normal lives.]

So, here’s what we see: a deeply indebted borrower trying to borrow more and wanting to extend its average maturity. That would be a red flag in any private sector deal.

Cue the “bond vigilantes.” Is it coincidence that long-term rates are rising and are rising the most in the part of the yield curve where the Treasury concentrates its debt? Probably not.

What’s happening, I suspect, is that Treasury debt is being repriced to reflect rising concerns about US fiscal stability. It’s not a panic yet; rates are still historically low, so far. The 10-year yield was in the 5% area and even up to 8% in the 1990s. Somehow the economy survived. But I think the rapid increase in rates for 5–10-year debt is a kind of warning shot. The bond vigilantes are telling Uncle Sam to get his act together.

Will he? We may know soon.

The last two days have seen long-term rates fall since the CPI number came in a little soft. This tells me the bond vigilantes will give the Trump team some time to demonstrate they are really serious about the deficit. How much time? We don’t know but the clock is ticking.

Juggling Act

We are now on the cusp of a leadership change in Washington. The administration whose increased spending produced the rising deficits is leaving, but it’s not clear if the new one will change direction. We see both hopeful and troublesome signs.

The “hopeful” case has several elements, including:

- The DOGE effort identifies a lot of wasteful programs and ways to improve efficiency, and Congress will pass legislation to address them.

- We avoid wars, recessions, pandemics, or other crises that would produce higher spending.

- Congress gets serious about reforming entitlement programs and has the votes to do it.

- Any tax cuts produce enough economic growth to replace the lost revenue.

The bond vigilantes don’t expect immediate results. They just want to see progress in the right direction and reasons to believe it will continue. Whether it can happen should become apparent in the next few quarters.

Of that list, entitlement reform is probably the hardest. Social Security and Medicare are rightly called the “third rails” of American politics. Touching them tends to vaporize career prospects. And even if Congress can agree on significant changes, they would probably need to be phased in over time… but time is running out. The bond vigilantes can be patient but not forever. A plan to start spending cuts 5–10 years from now won’t impress them.

Also troublesome is that achieving these miracles might still not be enough if other policy moves negate them. The president-elect continues talking about broad, punitive import tariffs. How much is real, how much is bluster, and how much is a negotiating tactic is anyone’s guess. This uncertainty has been rattling markets and may keep doing so. For what it’s worth, and it’s probably not worth very much, I think it’s largely a negotiating tactic. But a serious one, because Trump would have to be willing to actually back up his bluster.

Here’s my view: I think the bond vigilantes, business leaders, and other players fully expect some tariff activity. They understand the need to rebuild domestic production and restore balance. The concern is about how it’s done. They want to see a clear, orderly process with some degree of confidence in where it will end. Then they can plan accordingly.

If it turns into an opaque and chaotic process with no apparent end point, I think markets will rebel. The good news there is that Trump is keenly tuned into market reactions. I suspect he would get the message and change course.

A further complication is all this has to happen concurrently with other things. You may have noticed crude oil prices rising lately—from below $70 in late December to above $80 this week. The US imposed yet more sanctions on Russian oil exports and this time, it appears China isn’t coming to Putin’s rescue. Chinese ports have actually turned away some vessels carrying Russian oil. We hear reports from China that Xi and Trump are already talking. I think that’s good.

Combine this with the likelihood Trump will tighten the noose on Iranian oil exports, and the higher energy prices could last a while as he tries to make Putin withdraw from Ukraine. Prices could fall quickly afterward if OPEC countries reverse production cuts. Have you noticed how Trump has focused on Venezuela here and there? A change in Venezuela that allows oil exports to ramp back up while US producers turn up their dials should settle oil prices down over time. But meanwhile, rising energy prices could aggravate inflation.

Some inflation could actually help the debt situation. But it will also encourage the Fed to keep short-term rates higher for longer, raising the Treasury’s interest expense. It also hurts businesses and consumers who carry floating-rate debt or who have to refinance fixed debt at higher rates.

I had a long talk with my friend Barry Habib of MBS Highway yesterday on inflation and rates. Barry has won so many awards on his rates and inflation prediction prowess that there is really nobody else in second place. (As an aside, Barry has been going through a very serious fight with a very nasty cancer, involving multiple rounds of very high-tech and arduous therapies. His scans are finally coming clean and he looks and feels to be in good shape and is actually out on the road again traveling and speaking. His attitude and courage are truly inspiring.)

His firm does a very detailed prediction on various measures of inflation. He believes inflation will likely fall into the low 2 range by the end of the year because of the way housing prices are worked into the PCE model. They are not predicting 2% but close to it.

That would leave open the possibility of at least three and maybe even four 25-basis-point rate cuts in 2025. Combine that with some actual and substantial reductions in the deficit. Especially if the Trump administration actually follows through on regulatory relief, it would be very good for the economy and my sanguine 2025 forecast could remain intact.

I think we can expect the White House to get organized faster than they did in 2017, simply because they have more experience and will get their people in place more quickly. “At President Trump’s inauguration in 2017, he had filled 25 appointments (no typo) of the thousands of open spots required to be filled by the new administration. Going into next week’s inauguration, two thousand positions have been filled.” (h/t David Bahnsen)

I have talked to several of those appointees as they are my readers and friends. They don’t need the jobs and most have never really been in government, but they are going there with a genuine desire to try to improve things. They are truly focused on streamlining government, reducing regulations, and reducing costs. Nevertheless, if they don’t show progress on the debt, the bond market will eventually force the issue… and that won’t be good for anyone.

The timing is hard to predict. But if it quickly becomes obvious the deficit will keep growing, the “Partly Cloudy Year” I forecasted last week could get stormy fast.

That being said, I am optimistic. I think the appointments Trump is making really can make a difference. The biggest weakness in his rather ambitious plans are his very thin margins and fractious relationships in the House of Representatives. No bill is perfect. I am sure the House is going to pass bills that will curl my toes and likely yours as well.

As Reagan said, somebody that is with me 80% of the time is not my enemy. I hope they can keep that in mind. There is a short time to get a lot done and I wish them Godspeed.

Newport Beach, DC, and Dallas

I will be heading to Newport Beach for The Bahnsen Group’s annual client conference, and hopefully meet many readers there. I have penciled in a quick trip to the DC area to look at some facilities for potential meetings with doctors (Mike Roizen will come down) if all the schedules can align. And I know I have to be in Dallas sometime in March.

I had the flu for the first few days this week but am now better. I realize how lucky I am that I very seldom get sick, other than allergies and the usual aches and pains of getting older.

Getting to California is a long trip from Puerto Rico. It is your basic 12-hour travel day. Maybe I can get a chapter in my book written. But the quality of the conversations and the amount that I will learn makes it all worth it. Given the new startup and other projects, I will probably have to travel for this year more than I have for the past three or four years. Shane and I are even thinking Switzerland and Italy this summer for an actual vacation.

I am going to try to see more readers, and especially Alpha Society members. I really learn a lot and enjoy those meetings immensely.

And with that, it is time to hit the send button and wish you a great week!

Your cautiously optimistic about so many things analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply